Clinical Psychology and Cardiovascular Disease: An Up-to-Date Clinical Practice Review for Assessment and Treatment of Anxiety and Depression

Abstract

The aim of the present review is underline the association between cardiac diseases and anxiety and depression. In the first part of the article, there is a description of anxiety and depression from the definitions of DSM-IV TR. In the second part, the authors present the available tests and questionnaires to assess depression and anxiety in patients with cardiovascular disease. In the last part of the review different types of interventions are reported and compared; available interventions are pharmacological or psychological treatments.

INTRODUCTION

It is known that in patients with ischemic heart disease, anxiety and depression are predictive of adverse short- and long-term outcomes [1, 2]. In fact, patients who have anxiety or depression during hospital admission are at increased risk for higher rates of in-hospital complications such as recurrent ischemia, re-infarction and malignant arrhythmias [3, 4]. They also suffer higher mortality and re-infarction rates months to years after their initial cardiac event [4-7]. Anxiety disorders and depression are among the most prevalent psychiatric disorders [8]. Given the prevalence of anxiety and depression in the general population and in patients with Coronary Heart Disease [CHD], the potential public health impact for preventing the development and progression of CHD by appreciating the nature of the relationship between anxiety, depression and CHD is enormous [9]. Thus, it is clinically relevant in patient with cardiovascular disease to assess the psychological profile and treat emotional conditions that confer an increase risk of major adverse cardiovascular events.

ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION

Anxiety is a negative affective state resulting from an individual’s perception of threat and characterized by a perceived inability to predict, control or gain the preferred results in given situations [10]. Several studies suggest a relationship between anxiety disorders and increased cardiac outcomes [11]. Anxiety seemed to be an independent risk factor for incident CHD and cardiac mortality. Anxiety seemed to be an independent risk factor for incident CHD and cardiac mortality. The most recent meta-analysis [12] of references [1980 to 2009] on prospective studies of nonpsychiatric cohorts of initially healthy persons, in which anxiety was assessed at baseline, has shown as anxious persons were at risk of CHD [hazard ratio 1.26] and cardiac death [hazard ratio: 1.48], independently by demographic variables, biological risk factors, and health behaviors. In a much larger study [13], in subjects with no prior history of CHD, a dose-response relationship was found between phobic anxiety and coronary heart disease mortality [relative risk 2.5, 95% confidence interval 1.00 to 5.96]. Patients who are too anxious frequently are unable to learn or act upon new information about necessary life-style changes [14]. Moreover a recent Swedish 37years longitudinal study [4] which have investigated the long-term cardiac effects of depression and anxiety assessed at young age [18-20 years] according to International Classification of Diseases-8th Revision [ICD-8] criteria has been shown as anxiety is an independently predicted subsequent CHD events. Observations have shown a hazard ratios associated with anxiety of 2.17 and 2.51 for CHD and for acute myocardial infarction, respectively, against a corresponding hazard ratios associated with depression of 1.04 and 1.03. More recently the study by Zafar etal. [15] has examined, by a cross-sectional method, the effects of both depression and anxiety on platelet reactivity in a patient population with stable coronary artery disease. Findings show as subjects who were both depressed and anxious had significantly higher serotonin-mediated platelet aggregation compared with depressed-only subjects and subjects without affective symptoms. Anxiety and the mental stress associated with it contribute to excessive SNS activation and catecholamine release [16]. The bidirectional association between mood disorders and heart disease is multifaceted, involving an integration of several central and peripheral processes. On the base of the whole these data Wittstein [17] hypothesizes potential mechanisms of biological pathways between anxiety and serotonin to enhanced platelet activation. As indicated by DSM-TR [18] depression is a clinical syndrome defined by the presence of five out of nine follow criteria during the same 2-week period: depressed mood, diminished interest or pleasure in daily activities, significant unintentional weight change, sleep disturbance, psychomotor retardation or agitation, fatigue or loss of energy, feelings of worthlessness or excessive/inappropriate guilt, decreased ability to concentrate, and thoughts of death or suicide. Depression is associated with a odd ratio of 2 to 7 fold elevated risk of subsequent cardiac events, which is comparable to traditional cardiovascular risk factors such as hypertension [19-22] and this require a particular attention for the diagnosis.

The diagnostic difficulty of the depression in cardiac patient is due to atypical clinical presentation of depression in this patients and this explains the elevated percentage under-diagnosis of depression among cardiac patients. In 2008 the American Heart Association recommended [and the American Psychiatric Association endorsed] that “screening tests for depressive symptoms should be applied to identify patients who may require further assessment and treatment” if appropriate referral for further depression assessment and treatment is available. Depressive symptom dimensions after myocardial infarction [MI] may be differently related to prognosis. Somatic/affective [e.g., fatigue, sleep problems, and poor appetite] dimensions appear to be associated with a worse cardiac outcome than cognitive/affective dimensions [e.g., shame, guilt and negative self-image]. Specifically somatic/affective symptoms of depression [odds ratio: 1.49] it has been observed [23] to be related to a higher Killip class and mortality during the follow-up [12 months] period [odds ratio: 1.92]. These findings, which are in concordance with earlier studies [24-26], put further light on possible behavioral pathways which could explain the relationship between depressive symptoms and prognosis in ACS patients via unhealthy behavior, like smoking, less compliance, unhealthy diet and inactivity [27] and lack of physical activity [28].

ASSESSMENT OF ANXIETY AND DEPRESSION

Recently the American Heart Association [AHA], the American College of Cardiology, and the American College of Physicians highlight the need to adopt validated and easily performed screening test for depressions and anxiety in patients with cardiovascular disease [29, 30].

Physicians have to be acknowledge that the psychological risk is not uniform across all patients and that psychological factors might cluster together within individuals [31]. Currently, these individual differences are largely ignored in clinical research and practice, but they could be assessed with brief and standardized self-report measures and would do away with a single risk factor approach [32].

The Beck Depression Inventory [33, 34] is a self-report measure has 21 items grouped by diagnostic symptom [e.g., feelings of guilt, sadness, self-confidence and discouragement, loss of interest, crying, changes in appetite, sleep difficulties, suicidal ideation]. A cut-off score of 10 or greater identify the presence of depression. Scores at or above 10 are associated with poorer prognosis, whether for CHD progression [35] or “hard” medical endpoints such as death or myocardial infarction [36, 37]. Other symptom-based measure of depression used in cardiac patients are the Centers for Epidemiological Studies-Depression [CES-D] scale [38, 39], and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale [40]. To specifically assess exhaustion, the Maastricht Questionnaire can be used [41]. Also is available The Patient Health Questionnaire. The PHQ-9 is a nine-item tool, easy to administer and score. It has been well studied in both screening for and follow-up of depression in primary care [42, 43]. The PHQ-2 consists of the two first questions of the PHQ-9, which deal with mood and lack of pleasure. A cut-off score of 3 or higher has a sensitivity of 83% and a specificity of 92% [44], fulfilling the need for a quick and reliable depression screening tool. The clinician can also ask for a yes-or-no answer to the two questions of the PHQ-2. A yes to either of the two questions is up to 90% sensitive and 75% specific [43, 45]. Structured interviews are superior to questionnaires in differentiating dysthymia from Minor Depression. Based on the DSM- IV TR criteria, structured interviews have been developed to assess depression as Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV TR Axis I Disorders [SCID] and others [for review see [46]].

Patients with Acute coronary Syndrome [ACS] have many difficulties to emotional tolerate lengthy interviews specifically during the initial brief hospital stays. For this patients are indicated flexible clinical interviews conducted using an expressive-supportive method [47]. The Diagnostic Interview and Structured Hamilton [DISH] incorporates elements of other diagnostic and severity measures of depression, and is well suited for use with this population. It allows to establishment of an work alliance by discussing patient’s emotional experiences. The DISH scoring takes into account symptom severity and duration [46].

The American Heart Association [AHA] [48] released a consensus document recommending that health care providers screen for and treat depression and anxiety in patients with coronary heart disease. Also Pozuelo and colleagues [49] recommend that clinicians systematically screen for it in their heart patients, in view of the benefits of antidepressant therapy. Pozuelo and colleagues think that clinicians should routinely screen for depression in cardiac patients and should not hesitate to treat it and eligible patients should routinely be referred to cardiac rehabilitation programs [49].

As commented by Dimsdale [50] the recent observations on anxiety come at a time when psychiatry is once again redrawing diagnostic guidelines in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. To evaluate anxiety, simple screening questionnaires that have high reliability and validity are available. The Beck Anxiety Inventory [51], the Zung Self-Rating Anxiety Scale [52], or Hamilton Anxiety Scale [53] can be used as part of the routine workup of every patient. The Hamilton Anxiety Scale has the advantage of diagnosing depression as well as anxiety [53]. The major disadvantages in using the above scales are the time required for administration [15–25 minutes as part of a full battery], the need for scoring, and significant cost to purchase [29].

A newly useful created instrument, the Psychological General Well Being Index - 6 [PGWBI-6] was designed specifically for the outpatient cardiology setting [54-56] (see Table 1). This is a brief 6-item self-report measure that takes only minutes to perform and is highly correlated with other common scales and screens for anxiety, depressed mood, positive well-being, self-control, general health and vitality. The PGWBI score has shown to statistically be also correlated with cardiac rehabilitation outcome [56].

The Psychological General Well-Being Index [PGWBI-S] [29]

| 1. Have you been bothered by nervousness or your "nerves" during the past month? | |

| Extremely so – to the point where I could not work or take care of things | 0 |

| Very much so | 1 |

| Quite a bit | 2 |

| Some – enough to bother me | 3 |

| A little | 4 |

| Not at all | 5 |

| 2. How much energy, pep, or vitality did you have or feel during the past month? | |

| Very full of energy – lots of pep | 5 |

| Fairly energetic most of the time | 4 |

| My energy level varied quite a bit | 3 |

| Generally low in energy or pep | 2 |

| Very low in energy or pep most of the time | 1 |

| No energy or pep at all – I fell drained, sapped | 0 |

| 3. I felt downhearted and blue during the past month. | |

| None of this time | 5 |

| A little of the time | 4 |

| Some of the time | 3 |

| A good bit of the time | 2 |

| Most of the time | 1 |

| All of the time | 0 |

| 4. I was emotionally stable and sure of myself during the past month. | |

| None of the time | 0 |

| A little of the time | 1 |

| Some of the time | 2 |

| A good bit of the time | 3 |

| Most of the time | 4 |

| All of the time | 5 |

| 5. I felt cheerful, lighthearted during the past month. | |

| None of the time | 0 |

| A little of the time | 1 |

| Some of the time | 2 |

| A good bit of the time | 3 |

| Most of the time | 4 |

| All of the time | 5 |

| 6. I felt tired, worn out, used up, or exhausted during the past month. | |

| None of the time | 5 |

| A little of the time | 4 |

| Some of the time | 3 |

| A good bit of the time | 2 |

| Most of the time | 1 |

| All of the time | 0 |

Clinical Trials of Depression Therapy in Patients with Cardiac Diseases

| Trial | Therapies | Treatment Period | Results |

|---|---|---|---|

| M-HART [57] | Home nursing intervention [vs usual care] for psychological distress | 1 year | Prognosis: no improvement compared with usual care |

| Roose and colleagues [58] and Nelson and colleagues [59] | Nortriptyline vs paroxetine | 6 weeks | Depression: both effective Drug safety: nortriptyline toxic |

| ENRICHD [60] | Cognitive behavior therapy vs usual medical care | 11 sessions over 6 months | Depression: cognitive behavior therapy modestly effective Prognosis: no difference vs usual care |

| SADHART [61] | Sertraline vs placebo | 24 weeks | Depression: effective vs placebo Safety: safe |

| MIND-IT [62] | Mirtazapine vs placebo | 24 weeks | Depression: no difference vs placebo Prognosis: no difference vs placebo |

| CREATE [63] | Citalopram ± Interpersonal psychotherapy | 12 weeks | Depression: citalopram effective; interpersonal psychotherapy not effective |

The advantage of the PGWBI-6 is that only 1 scale is required to screen for all of these risk factors, and it can be filled out easily by the patient as part of the initial work up. The results can be quickly analyzed by a nurse or the cardiologist and is available for no charge. These scales provide data that can quickly lead to treatment decisions regarding mental health care. The screening can serve to delineate normal levels of anxiety and depression from more pathologic levels [29].

Because anxiety can have neurobiologic, behavioral, and cognitive/psychologic correlates, it is imperative that cardiologists accurately elicit symptoms of anxiety in the history and via screening that draw upon these 3 domains. The treatment of depression is articulated in three phases: 1) acute phase; purpose: to reduce symptoms [6-12 weeks]; 2) continuation phase; purpose: prevent relapse [4-9 months]; and 3) maintenance phase; purpose: long-term treatment outcome [22].

TREATMENT

Pharmacological Interventions

Pharmacological treatment of depression in patients with CHD is complex and entails certain limitations and contraindications [47]. Table 2 shows the clinical trials of depression therapy in patient with cardiac diseases.

Selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors [SSRI] tend to be tolerated better than the traditional tricyclic antidepressants [TCA] [58]. SSRIs have been found effective for treating depression in this population [61]. However, most SSRIs should not be used in combination with class IC anti-arrhythmics and may also potentiate the effects of beta-adrenergic blocking agents. Furthermore, SSRIs appear to reduce depressive symptoms but depression tends not to completely remit in patients with CAD [Coronary Artery disease]. The Myocardial Infarction Depression Intervention Trial [MIND-IT] [64] looked at whether the antidepressant mirtazapine [Remeron] would improve long-term depression and cardiovascular outcomes in depressed post-MI patients. In 18 months of follow-up, neither objective was obtained. The Cardiac Randomized Evaluation of Antidepressant and Psychotherapy Efficacy [CREATE] trial [63] tested the efficacy of the SSRI citalopram [Celexa] and interpersonal therapy in a short-term intervention. Here, the antidepressant was superior to placebo in the primary outcome of treating depression, but interpersonal therapy had no advantage over “clinical management,” ie, a shorter, 20-minute supportive intervention [49].

Psychological Interventions

Cognitive behavioral therapy is often successfully used in the treatment of depressive disorders [47]. The main goal of this approach is to modify dysfunctional thoughts and emotions by structured and empathic questioning of patients’ perceptions and thought processes [60]. The typical duration of psychological interventions in CAD patients ranges from 8 to 12 weeks [65-68]. Sebregts and colleagues [69] intended to develop a relatively short intervention program of 8 weeks, accessible for a large group of AMI [Acute myocardial infarction] and coronary artery bypass grafting [CABG] patients. This intervention explicitly addressed multiple modifiable risk factors. It was directed at the reduction of psychological stress/distress [Type A behavior in particular], the reduction of excessive consumption of dietary fat, elevated serum cholesterol, lack of physical exercise, and although less explicitly—smoking and insufficient social support through the involvement of the patients’ partners in the intervention [68]. The results of this study show that Type A behavior can be reduced in coronary patients through a relatively short intervention program aimed at behavior change and risk reduction. Although No favorable effects were found on depression or vital exhaustion. In view of the findings on the diagnosis of depression, researchers do not unequivocally advise the intervention to the general population of AMI and CABG patients [69]. Other behavioral medicine group programs have attempted to incorporate stress management, relaxation training/cognitive behavior therapy and lifestyle modification for heart disease including Ornish's Lifestyle Heart Trial [70, 71] and the Recurrent Coronary Prevention Project [72] for reducing Type-A behavior. In the case of the former, actual regression of coronary artery stenosis was achieved in 1-year, and 4- and 5- year follow-up studies in those participants who maintained the lifestyle changes [73]. A recent study of an integrative medicine approach applied to cardiac risk reduction demonstrated that after 10 months of a personalized health plan consisting of mindfulness meditation, relaxation training, stress management, and health education and coaching, patients in the active treatment group had lowered risk, lost more weight, and exercised more frequently compared with the usual care group [74]. Overall behavioral medicine group programs have been shown to reduce the cost of unnecessary medical procedures and work-ups [especially related to anxiety], improve complain with treatment, and reduce the risk factors of stress and an unhealthy lifestyle [75]. As well because these are group interventions this helps patients overcome stigma, social isolation and learn how to better manage their anxiety and depression.

Also for anxiety, cognitive behavior therapy, a well-documented evidence-based treatment, should be instituted at the beginning of treatment to ensure that patients understand their condition and that medication management is only one aspect of their treatment [76]. In cognitive behavior therapy, patients are taught to restructure anxiety-provoking thoughts leading to panic attacks, are taught relaxation techniques to counteract stress and anxiety, and are given exposure therapy to desensitize themselves to stressful stimuli. Cognitive behavior therapy is also extremely useful and effective in teaching anger management skills when treating Type A behavior pattern [TABP personality] [77]. Cognitive behavior therapy conveys the message to the patient that it is possible to learn self-management techniques and methods that will most likely allow them to discontinue medications within 6 months to 1 year. Other forms of psychotherapy, such as psychoanalytic, interpersonal, and supportive therapies, can be effective as adjunctive therapies, but do not carry the wealth of evidence-based research demonstrating their effectiveness in the treatment of anxiety disorders.

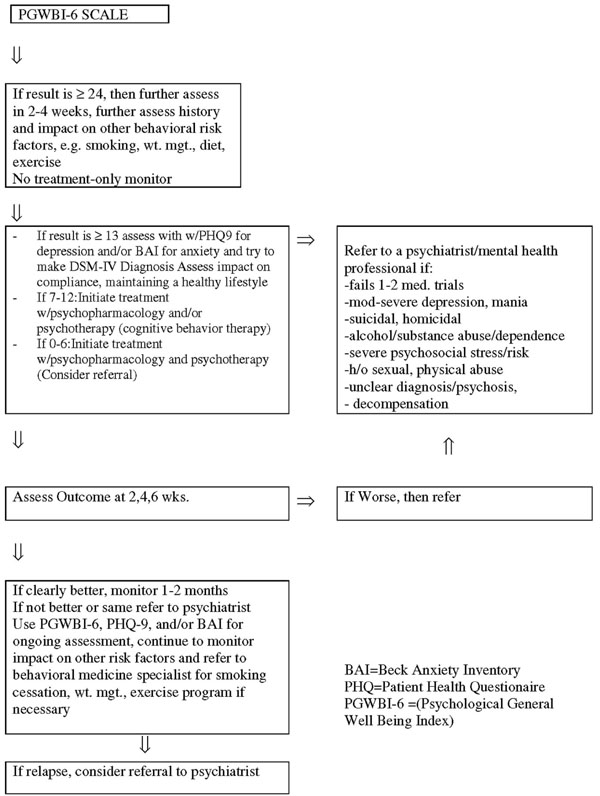

A new proposed anxiety and depression treatment algorithm is based on PGWB initial screening (see Fig. (1)).

Anxiety and depression treatment algorithm [29].

As seen in the algorithm (see Fig. (1)), when the screening identifies patients who have more than mild anxiety and depression and have failed 1-2 medication trials, have suicidal or homicidal ideation or a history thereof, alcohol/substance abuse, mania or psychosis, history of sexual, physical abuse, or severe psychosocial distress, a referral should be made to a mental health professional. Integrating ongoing assessments reduces the stigma of mental illness and leads to the greater likelihood of patients receiving adequate mental health treatment. This strengthens the treatment alliance and can improve compliance with medical treatment.

Among the psychotherapies, cognitive behavior therapy [CBT] and interpersonal psychotherapy [IPT] are the most effective, in both acute and maintenance treatments [78]. Interpersonal psychotherapy is a time-limited [12-16 weekly 1-hour sessions] manualized psychotherapy that was developed in the early 1970’s by Gerald Klerman and colleagues as a research intervention for outpatients with unipolar major depression [79]. Interpersonal psychotherapy is based on the presumption that interpersonal issues affect mood and mood impairs interpersonal functioning. Interpersonal psychotherapy has been extensively researched and shown to be effective as both an acute and preventive treatment for major depressive disorder [80]. IPT conceptualizes clinical depression as having three component processes: symptom formation caused by biological and/or psychological mechanisms; social functioning [involving, obviously, social interactions with others]; and enduring personality traits [81]. IPT intervenes in symptom formation and social dysfunction but does not address enduring personality traits in view of the time limits of treatment, the relatively low level of psychotherapeutic intensity, the emphasis of treatment on the current depressive episode, and the difficulty in accurately evaluating personality in the midst of an Axis I disorder [82]. The brevity of the treatment imposes a structure that pressures the patient and therapist to work quickly to alleviate depressive symptoms and resolve the current interpersonal crisis linked with the depression, thus discouraging the patient’s becoming dependent on the therapist [81]. For each patient, therapy focuses on one or, at most, two interpersonal problem areas that are identified as precursors of the current depressive episode. These problem areas were derived from extensive research on the role of environmental influences on mood and are characterized as unresolved grief following the death of a loved one, role transitions [difficulty adjusting to changed life circumstances], interpersonal role disputes [conflicts with a significant other] and interpersonal deficits [impoverished social networks]. Maintaining the focus of treatment on a problematic interpersonal issue prevents the therapy from becoming too diffuse and forces the therapist and patient to discuss material that is relevant to the focal area and treatment objectives [81]. IPT also focuses on the “here and now,” that is, on current problematic interpersonal issues that are amenable to change, rather than on reconciling unresolved interpersonal problems having to do with the past. The focus on resolving current interpersonal problems and developing strategies for warding off future problems helps reduce the depressed patient’s tendency to ruminate about past events and experiences that cannot be changed and which only serve to reinforce the patient’s already low sense of self-esteem and dysphoria [81]. The primary goal of IPT is to obtain the remission of depressive symptoms by facilitating resolution of a current interpersonal crisis. At one-year follow-up, patients who received interpersonal psychotherapy had better psychosocial functioning than those who did not receive this treatment [83]. The National Institute of Mental Health Treatment of Depression Collaborative Research Program [NIMH TDCRP] found that, in general, interpersonal psychotherapy is an effective monotherapy for patients with mild to moderate depression, but that antidepressant medication should be used as a first line treatment for severely ill patients.

CONCLUSION

Despite the large amount of evidence supporting significant and independent associations between anxiety and depression and the pathogenesis of cardiovascular disease, the 2010 American College of Cardiology Foundation/American Heart Association Guideline for Assessment of Cardiovascular Risk in Asymptomatic Adults [84, 85] does not consider yet any of them.

Further research is warranted to determine factors that may moderate anxiety in order to better understand the phenomenon among acute myocardial infarction patients and develop effective interventions. It appears that anxiety after acute myocardial infarction is a universal phenomenon [9]. Future studies need to disentangle the cause effect relationships between depression, anxiety and adverse health behaviors in patients with coronary artery disease [30]. As commented on by Dimsdale [50] the recent findings regarding anxiety come at a time when psychiatry is once again redrawing diagnostic guidelines in the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual. For decades, the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual has differentiated between anxiety disorders and depressive disorders but in clinical practice these disorders rarely occur in isolation and the distress associated with them increases synergistically when both sets of symptoms coexist. Future researches should analyze together the two symptoms and their synergic action in heart disease. It would be useful for clinical practice to develop treatments that combine strategies for anxiety and depression and evaluate whether such treatments would reduce cardiovascular risk [86].

Depression can be treated effectively with a combination of psychological and pharmacological interventions [57]. Also anxiety is common among cardiac patients and should be treated to enhance recovery and decrease patients’ risk of subsequent cardiac events. One of the most important areas for future research is elucidating the mechanisms whereby anxiety causes poorer outcomes in acute myocardial infarction patients. The mechanisms [either physiological or behavioral] whereby anxiety is related to poorer short and long term outcomes in acute myocardial infarction patients have yet to be elucidated. Research in this area is important to help clinicians determine the best ways to manage acute myocardial infarction patients to decrease the negative impact of anxiety [9].

In future trials, it is important to pay particular attention to nonresponders to intervention, because these patients have been shown to be at a higher risk of late mortality compared with responders [87]. If we are to continue lowering the rates of CHD, we have to continue to emphasize prevention of the modifiable risk factors. This will require that cardiologists, cardiovascular surgeons and mental health professionals work together to provide comprehensive treatments that address not only CHD but optimize the mental health of patients.