All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Repetitive Transcranial Magnetic Stimulation (rTMS) to Treat Social Anxiety Disorder: Case Reports and a Review of the Literature

Abstract

Objectives: Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is a common and debilitating anxiety disorders. However, few studies had been dedicated to the neurobiology underlying SAD until the last decade. Rates of non-responders to standard methods of treatment remain unsatisfactorily high of approximately 25%, including SAD. Advances in our understanding of SAD could lead to new treatment strategies. A potential non invasive therapeutic option is repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS). Thus, we reported two cases of SAD treated with rTMS Methods: The bibliographical search used Pubmed/Medline, ISI Web of Knowledge and Scielo databases. The terms chosen for the search were: anxiety disorders, neuroimaging, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation. Results: In most of the studies conducted on anxiety disorders, except SAD, the right prefrontal cortex (PFC), more specifically dorsolateral PFC was stimulated, with marked results when applying high-rTMS compared with studies stimulating the opposite side. However, according to the “valence hypothesis”, anxiety disorders might be characterized by an interhemispheric imbalance associated with increased right-hemispheric activity. With regard to the two cases treated with rTMS, we found a decrease in BDI, BAI and LSAS scores from baseline to follow-up. Conclusion: We hypothesize that the application of low-rTMS over the right medial PFC (mPFC; the main structure involved in SAD circuitry) combined with high-rTMS over the left mPFC, for at least 4 weeks on consecutive weekdays, may induce a balance in brain activity, opening an attractive therapeutic option for the treatment of SAD.

INTRODUCTION

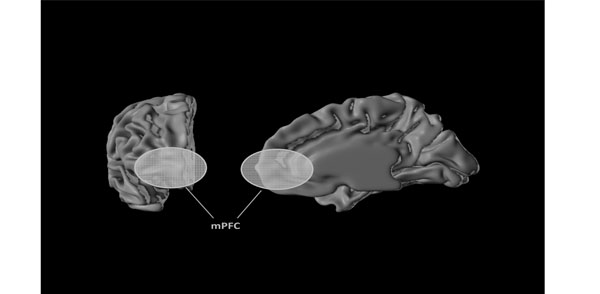

Social anxiety disorder (SAD) is one of the most common anxiety disorders, characterized by fear and avoidance of social situations [1]. SAD can be divided into two subtypes: specific and generalized SAD. Specific SAD refers to the fear and avoidance of a particular performance situation such as public speaking, while generalized SAD refers to fear and avoidance of a wide array of social situations, with subsequently stronger impairing effects as compared to specific SAD [1]. SAD is very debilitating and despite its high prevalence [2, 3], little attention had been dedicated to the study of the neurobiology underlying SAD until the last decade [4]. However, with the considerable increase in the number of studies in the last years, aiming to elucidate the physiopathological aspects of SAD [5,6], together with clinical reports, animal models, genetic [7], and neuroimaging studies, a better comprehension of the neural circuitry underlying SAD has been achieved [8]. external view of the right mPFC while the right image shows an internal projection of the right mPFC, the main brain structure related to social anxiety disorder.

Anxiety disorders have a lifetime prevalence of greater than 20%, and although there are several methods of treatment available (i.e., pharmacotherapy and cognitive-behavioral therapy), high rates of non-responders to these treatments are reported, namely, approximately 25%, including SAD [9, 10]. Thus, searching for new alternative treatments is essential. Advances in our understanding of the neurobiological mechanisms involved in SAD could lead to new therapeutic options. One such novel therapeutical option is repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation (rTMS), a non-invasive procedure whereby a pulsed magnetic field stimulates electrical activity in the brain and depolarizes neurons [11]. rTMS can be considered a brain-system-based neuromodulation treatment due to its ability of directly targeting the neural circuitry of several psychiatric and/or neurological disorders [12]. rTMS shifts the perspective of treatment from changing the neurochemistry within the synapse; to altering or modulating the function of the neural circuitry in the brain that is believed to be disorganized in case of certain disorders [9,10,12].

However, until today, there is no consensus about the brain circuitries underlying SAD. Several studies have reported the participation of amygdala, medial frontal cortex, insular cortex, and cingulate cortex [13,14]. However, a recent systematic review [1] stated that medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC) is the structure most consistently activated in all studies on SAD (Fig. 1). Hence, the mPFC represents a promising candidate region for being targeted with a non-invasive brain stimulation technique such as rTMS.

The medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC). The left image shows the frontal pole of the right brain hemisphere, the yellow mark is the external view of the right mPFC while the right image shows an internal projection of the right mPFC, the main brain structure related to social anxiety disorder.

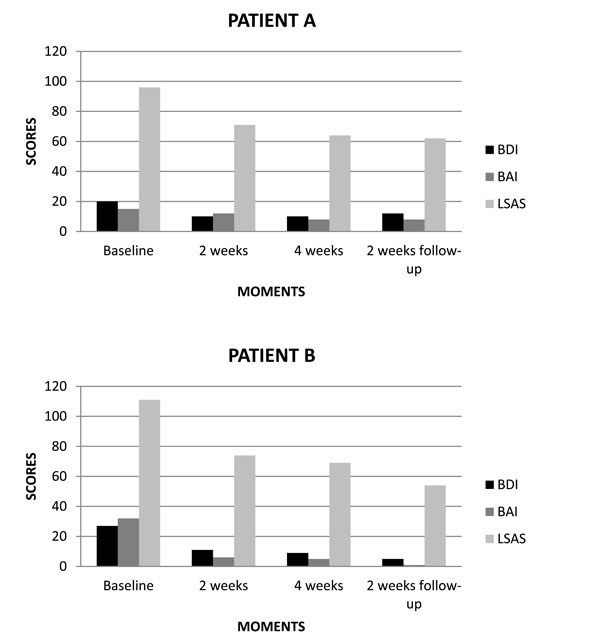

(A, B) Scores of BDI, BAI and LSAS related to rTMS treatment for SAD patients.

This review aims to provide information on the current research and main findings related to brain circuitries involved in SAD, rTMS protocols used for treating anxiety disorders, the rationale of rTMS on Social Phobia treatment and two cases of SAD treated with rTMS. Thus, we hypothesize that the optimal rTMS regime for treating SAD, based on the “valence hypothesis”, is to use low-rTMS over the right mPFC.

METHODS

With this in mind, we developed a strategy for searching studies in the main data bases. The computer-supported search used the following databases: Scielo, Pubmed/Medline, ISI Web of Knowledge, PsycInfo and Cochrane Library. The search terms Panic disorder, Obsessive-Compulsive disorder, Post-traumatic stress disorder, Generalized anxiety disorder, Social anxiety disorder were used in combination with transcranial magnetic stimulation, TMS, repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation, rTMS, motor threshold, motor evoked potential, MEP, cortical excitability, neuroimaging. In addition, all reports including reviews, metaanalyses and controlled randomized clinical trials and open label trials, book chapters are also cited to provide readers with more details and references than can be accommodated within this paper. Discussion has been focused mainly on studies published in English and reported in the past 12 years but also included commonly referenced studies relevant to the neurobiology of the diseases and possible rationales for rTMS application in Social Phobia.

BRAIN CIRCUITRIES INVOLVED IN SOCIAL ANXIETY DISORDER

Neuroimaging techniques allow for an in vivo assessment of the functional architecture of the human brain, leading to a better understanding of its anatomical and functional state [15]. Up to the last decade, little attention had been dedicated to neurobiological mechanisms underlying SAD, however, it has been demonstrated that the identification and location of abnormal brain functioning depend on the type of anxiety disorder [8].

Several neuroimaging studies have demonstrated that amygdala and mPFC play a key role in the attribution of emotion-related stimuli in SAD [16-19]. Generally, these findings suggest a deficit in top-down modulation of executive processes, such as associative, attentional and interpretative control [20]. In theory, the abnormal functioning of circuitries in SAD would result in impaired top-down modulation, i.e., impairment in the connectivity and cross-talk between amygdala and prefrontal brain areas. Prefrontal areas, which are also responsible for inhibitory responses, could lead to increased responsiveness of the amygdale [21].

Based on results from animal studies, Bishop [22] proposed that a down regulation of amygdala output may be brought about by two distinct process: i) through an excitation of gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) pathways within the basolateral complex of the amygdala, or ii) through an excitation of the nearby intercalated cells via mPFC neurons. In line with this view, clinical and neuroimaging results have demonstrated that selective attention is associated with emotion-related stimuli involved in dysfunctional prefrontal inhibition, and with amygdala hyperactivity during the processing of potentially threatening information from the environment [23, 24].

There is also evidence of decreased activity in prefrontal areas during anxiety provocation in patients with SAD, probably reflecting impaired cognitive processing [25-28], and increased activity in prefrontal areas during provoked anticipatory anxiety [29, 30]. There are two rationales for these apparent discrepancies: i) functional responses of the mPFC are dependent on the nature of the cognitive-emotional task employed [31] and ii) the mPFC is subdivided into distinct neuroanatomical and functional areas [32]. In a similar vein, several studies have concretely proposed that the mPFC can be functionally divided into two different parts: i) a ventral region, mainly related to self-referential/relevant processing [33, 34] and ii) a dorsal region, related to theory of mind, such as contemplating about other people's mental states [35, 36]. The study of Blair et al. [37] used functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) to reveal that SAD patients had significant responses to self-referential criticism in more dorsal regions of the cortex. These findings regarding mPFC subregions could be used as a guide for new investigations in SAD, using neuroimaging methods and specific cognitive tests. Amir et al. [38], e.g., demonstrated an association between anterior cingulated cortex (ACC) (i.e., a part of the mPFC) and the negative emotion in SAD patients viewing disgusted facial expressions. The dorsal ACC is thought to recruit the dorsolateral mPFC in order to select and implement regulatory strategies, directing attention control, and reducing cognitive conflicts [39]. Therefore, impairment of early recruitment of dorsal ACC and dorsolateral mPFC during cognitive reassessment could trigger emotion regulation problems in SAD patients [40].

RTMS PROTOCOLS USED FOR TREATING ANXIETY DISORDERS

A few studies have been conducted in order to investigate the therapeutic effects of rTMS on anxiety disorders, but not on SAD (see Table 1). Even though positive effects have been found in both, controlled and non-controlled studies, there are still no established protocols for rTMS treatment in anxiety disorders. Perhaps the lack of standard rTMS treatment may be due to the varying treatment parameters used in these studies, making the interpretation of the results difficult [10].

Summary of Open and Controlled Studies of rTMS and its Effects on Anxiety Disorders

| Study OCD | Design | N | rTMS Protocol | Efficacy |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Greenberg et al. 1998 | Open study 1 session | 12 | PFC-R 20Hz of 80% MT PFC-L 20Hz of 80% MT Occipital 20Hz 80% MT |

Reduction in OCD symptoms only with right-sided treatment.* |

| Sachdev et al. 2001 | Open study 10 sessions (5 days per week for 2 weeks) | 12 | PFC-R 10Hz of 110%MT PFC-L 10Hz of 110% MT |

Both groups showed a significant reduction in OCD symptoms.* However, no significant difference was noted between groups. |

| Alonso et al. 2001 | RCT 18 sessions (3 days per week for 6 weeks) | 18 | DLPFC-R 1Hz of 110% MT Sham-rTMS |

Slight reduction in OCD symptoms in rTMS group.* However, no significant difference was noted between groups. |

| Mantovani et al. 2006 | Open study 10 sessions (5 days per week for 2 weeks) | 10 | SMA-bilaterally 1Hz of 100% MT | Significant reduction in OCD symptoms.* |

| Prasko et al. 2006 | RCT 10 sessions (5 days per week for 2 weeks) | 30 | DLPFC-L 1Hz of 110% MT Sham-rTMS |

Both groups showed a significant reduction in anxiety.* However, no significant difference was found between groups. |

| Sachdev et al. 2007 | RCT 10 sessions (5 days per week for 2 weeks) | 18 | DLPFC-L 10Hz of 110% MT Sham-rTMS |

No significant difference was found between groups. However, after comparison, all subjects received rTMS showed a significant reduction in OCD symptoms. |

| Kang et al. 2009 | RCT 10 sessions (5 days per week for 2 weeks) | 20 | DLPFC-R 1 Hz of 110% MT SMA-bilaterally 1Hz of 100% MT Sham-rTMS |

No significant difference was found on both groups and between groups. |

| Ruffini et al. 2009 | RCT 15 sessions (5 days per week for 3 weeks) | 23 | OFC-L 1Hz of 80% MT Sham-rTMS |

Significant reduction in OCD symptoms in favor of rTMS compared to sham-rTMS.* However, no significant reduction in anxiety and depression symptoms was found between groups. |

| Mantovani et al. 2010 | RCT 20 sessions (5 days per week for 4 weeks) | 18 | SMA-bilaterally 1Hz of 100% MT Sham-rTMS |

Significant reduction in OCD symptoms in favor of rTMS compared to sham-rTMS.* |

| Sarkhel et al. 2010 | RCT 10 sessions (5 days per week for 2 weeks) | 42 | PFC-R 10Hz of 110% MT Sham-rTMS |

Significant reduction in OCD symptoms and a significant improvement in mood in both groups.* However, no significant difference was observed between groups. |

| PTSD | ||||

| Grisaru et al. 1998 | Open study 1 session | 10 | Motor cortex-R of 0.3 Hz of 100% MT Motor cortex-L of 0.3 Hz of 100% MT |

Significant reduction in anxiety, and PTSD symptoms.* |

| Rosenberg et al. 2002 | Open study 10 sessions (5 days per week for 2 weeks) | 12 | DLPFC-L 1Hz of 90% MT DLPFC-L 5 Hz of 90% MT |

Significant improvement of insomnia, hostility and anxiety, but minimal improvements in PTSD symptoms.* However, no significant different was noted between groups. |

| Cohen et al. 2004 | RCT 10 sessions (5 days per week for 2 weeks) | 24 | DLPFC-R 1Hz of 80%MT DLPFC-R 10Hz of 80%MT Sham-rTMS |

Significant improvement of PTSD symptoms and a significant reduction in general anxiety levels in favor of 10Hz-rTMS group when compared to other groups.* |

| Boggio et al. 2010 | RCT 10 sessions (5 days per week for 2 weeks) | 30 | DLPFC-L 20Hz of 80%MT DLPFC-R 20Hz of 80%MT Sham-rTMS |

Significant reduction in PTSD symptoms, anxiety and improvement of mood in favor of rTMS compared to sham-rTMS.* |

| PD | ||||

| Prasko et al. 2007 | RCT 10 sessions (5 days per week for 2 weeks) | 15 | DLPFC-R 1Hz of 110% MT Sham-rTMS | Both groups showed a significant reduction in anxiety symptoms.* However, no significant difference was found between groups for PD symptoms. |

| GAD | ||||

| Bystrisky et al. 2008 | Open study 6 sessions (2 days per week for 3 weeks) | 10 | DLPFC-R 1Hz of 90% MT | Significant reduction in anxiety symptoms.* |

* Significant level at ≤ 0.05

DLPFC: dorso lateral prefrontal cortex; L: left; GAD: generalized anxiety disorder; MT: motor threshold; OCD: obsessive compulsive disorder; PD: panic disorder; PTSD: posttraumatic stress disorder; R: right; RCT: randomized clinical trial; rTMS: repetitive transcranial magnetic stimulation; SMA: supplementary motor area.

The first evidence of a putative anxiolytic action of rTMS in humans was based on the so called ‘‘valence-hypothesis’’ [41], which has been proposed for human anxiety. According to this model, patients with anxiety disorders are characterized by an interhemispheric imbalance that might be associated with increased right-hemispheric activity [9, 10].

First empirical support for this model was reported by two studies applying 1 Hz-rTMS over the right prefrontal cortex (PFC) [42, 43]. They demonstrated anxiolytic effects of slow-frequency rTMS over the right mPFC after inducing anxiogenic states in healthy individuals. In contrast, other studies examined the hypothesis that not low- but high-frequency-rTMS over the left dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC) is effective in the treatment of anxiety disorders [44, 45], a rationale that is supported by the cerebral hyperexcitability and the behavioral and cognitive activation that is commonly observed in neuropsychiatric disorders [46]. The activity of fronto-subcortical circuits can arguably be diminished by increasing the activity in the indirect pathway by stimulating the left DLPFC with high-rTMS [44, 45].

Several controlled and non-controlled TMS studies in anxiety disorders have recently been reported, with the use of either low- and/or high-frequency rTMS applied to either left and/or right hemisphere, especially in PFC areas, such as the DLPFC and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC). Intriguingly, despite the fundamental differences in rTMS frequencies that were used and/or hemispheric lateralization that was targeted, all of these studies demonstrate promising positive effects with regard to a TMS-induced reduction of anxiety symptoms. Concretely, six studies explored active-rTMS over the right hemisphere, with two stimulating with high-frequency rTMS [47, 48] and four with low-frequency rTMS [49-52]. Three studies explored active-rTMS over the left hemisphere, with one stimulating with high-frequency rTMS [53] and two with low-frequency rTMS [54, 55]. In addition, one study compared the low- and high-frequencies in the right hemisphere [56] and another study did so for the left hemisphere [57]. Again two studies applied high-frequency rTMS over both hemispheres [58, 59]. However, only few studies demonstrated statistically significant differences between active and sham treatment [47, 55, 56].

Hence, although positive results have frequently been reported in both non-controlled and controlled studies, there is no conclusive evidence of the efficacy of rTMS for the treatment of anxiety disorders. Several, sometimes contradictory, treatment parameters have been used in the different studies, making the interpretation of the results difficult. Most studies, therefore, do not support the notion that active-rTMS, as hitherto applied, is an effective treatment for obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD) and posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD). In the literature on the therapeutic effects of rTMS in depression, it is clearly suggested that 4 weeks (i.e., 20 sessions) of rTMS administered on consecutive weekdays are necessary for achieving consistent antidepressant effects. In contrast, only three TMS studies on anxiety disorders have assessed the effects of rTMS compared to sham-rTMS over at least 4 weeks [49, 55, 60]. Moreover, in one of these studies, rTMS was only given five-times per week by Ruffini et al. [55]. Two other studies may have been underpowered, suggesting that results could be attributed to a type II error [49, 54], and probably due to the low placebo response reported in patients. In line with this notion, Sachdev and colleagues [53] inferred that, given the effect size in their study, a very large sample would have been required to demonstrate a significant group difference.

Sham-controlled research has often been unable to distinguish between response to rTMS and sham treatment. Within this context, all sham-controlled studies used methods that are recognized to provide adequate blinding (i.e., active coil, 45° or 90° to the head or inactive coil on the head with active coil discharged in 1 m-distance) [47-49, 51, 52, 54-56, 59]. However, only 4 studies showed significant differences between rTMS and sham treatment [47, 55, 56, 60].

Moreover, only four studies controlled for antidepressant effects [47, 48, 54, 55]. This is important, since application of rTMS to the PFC can have antidepressant effects [61,62] and since comorbid depression is common in patients with anxiety disorders [63]. As such, it is very difficult to assess the effects of rTMS on anxiety disorders independent of depression.

Finally, there is a limitation in the rTMS technique itself which impacts only the superficial cortical layers directly. It is possible to also affect more distant cortical areas and also subcortical areas, relevant to the pathogenesis of anxiety disorders, though such effects in subcortical areas are thought to be indirect, via trans-synaptic connections [9, 10, 44, 64].

With regard to theoretical conceptualizations, the reported effects of rTMS over right PFC for reducing anxiety symptoms are possibly brought about by re-establishing the connectivity between an underactive PFC, which is theorized to mediate amygdala activity and amygdala hyperactivity, by increasing PFC activity, suggesting that high-rTMS might be an optimal treatment strategy. Alternatively, these results could be associated with increased activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis, suggesting an association between right prefrontal and HPA axis hypoactivity. Given the effects of rTMS in depression, stimulation in the right PFC with high frequency would then theoretically worsen depressive symptoms that are generally comorbid, since hyperactivity of the HPA axis is commonly implicated in the pathogenesis of depression [65].

The findings of antidepressant effects of rTMS application over the left hemisphere with are to be expected due to comorbidity with depression often observed in patients with anxiety disorders. However, the findings regarding the effects of rTMS application over these areas do not support the hypothesis that the activity of fronto-subcortical circuits can be diminished by increasing the activity in the indirect pathway by stimulating areas of the left hemisphere, mainly the DLPFC, by high-rTMS [44, 45].

RTMS AND SOCIAL PHOBIA: WHAT IS THE RATIONALE?

While the main focus of the possible therapeutic effects of TMS has been mainly in the domain of depression, there are now a significant number of studies that have explored the possibility of using rTMS for treating anxiety disorders. In most of these studies, both, non-controlled and controlled, in which the right PFC, more specifically the DLPFC was stimulated, conflicting results were found in comparison with the studies that investigated the effects of rTMS in the left OFC, PFC and DLPFC. However, only two controlled studies demonstrated positive effects, more specifically with high-rTMS application, supporting the idea that modulating the right PFC or DLPFC with high-rTMS might be an optimal treatment strategy, due to the possibility of re-establishing the connectivity between an underactive PFC, which is theorized to mediate amygdala activity and amygdala hyperactivity, by increasing PFC activity [47, 56].

However, this rationale contradicts the valence hypothesis. According to this hypothesis, anxiety disorders are characterized by an interhemispheric imbalance, with increased right-hemispheric activity [41, 66]. Thus, would be rTMS a future treatment for social phobia?

With regard to Social Phobia, at the moment, there is only one case report published [67]. In this case report, we found that one session of 1Hz-rTMS over the right ventromedial prefrontal cortex (vmPFC) for 25 min (1500 pulses) improved moderately the anxiety levels and mildly the social skills abilities and that these effects remained after two-months follow-up.

In line with this, we conducted 2 new case reports. The patients A and B were diagnosed with generalized SAD, with comorbidity depression according to DSM-IV-TR. The patient A (23 years old) had 60 mg per day of fluxetine and 2.5 mg per day of clonazepam during two months, was treatment-resistant to cognitive behavior therapy (CBT). The patient B (45 years old) was treatment-resistant to serotonin-specific reuptake inhibitor (SSRI) and CBT. The treatment protocol of rTMS was administered at 1Hz (inhibitory frequency) 120% MT for 25 min (1500 pulses), 3 times per week during 4 weeks over the right vmPFC, structure most consistently activated on SAD [1], representing promising targeted region for rTMS application. Right vmPFC is located near to Fp2 position according to EEG-international 10/20 electrode scalp positioning system. Through this system, satisfactory activation of cortex areas may be reach reliably on a larger scale level [68]. Patients were assessed in baseline, 2 weeks, 4 weeks and after 2 weeks follow-up using the Beck Depression Inventory (BDI), Beck Anxiety Inventory (BAI) and Liebowitz social anxiety scale (LSAS).

In the first case, i.e. patient A (male), we found in baseline the following results: BDI 20 (moderate), BAI 15 (minimal) and LSAS 96 (very severe). After two weeks of treatment, we noted the following results: BDI 10 (minimal), BAI 12 (minimal) and LSAS 71 (moderate). At the end of treatment, we verified the following results: BDI 10 (minimal), BAI 8 (minimal) and LSAS 64 (moderate). On two weeks follow-up, we obtained the following results: BDI 12 (minimal), BAI 8 (minimal) and LSAS 62 (moderate) (Fig. 2A).

Before rTMS treatment, patient presented very severe level of social anxiety, observed in LSAS, reporting for example, meeting strangers, entering a room when others are already seated (areas most highly rated on LSAS; assessment point level 3). Two and four weeks after rTMS treatment and after 2 weeks follow-up, patient showed large reduction in social anxiety symptoms (areas most highly rated on LSAS; assessment point level 1- minimal) compared to baseline. With regard to BAI, patient presented severe level of anxiety in baseline, reporting for example, unable to relax, heart pounding/racing (areas most highly rated on BAI; assessment point level 2). Two and four weeks after rTMS treatment and after 2 weeks follow-up, patient showed large reduction in anxiety symptoms (areas most highly rated on BAI; assessment point level 1- minimal) compared to baseline. At last, we observed in BDI that patient had moderate depressive symptoms in baseline, reporting for instance, I feel the future is hopeless and that things cannot improve, I feel I am being punished (areas most highly rated on BDI; assessment point level 3). Two and four weeks after rTMS treatment and after 2 weeks follow-up, patient showed large reduction in depressive symptoms (areas most highly rated on BDI; assessment point level 0 - no depression) compared to baseline.

In the second case, i.e. patient B (female), we found in baseline the following results: BDI 27 (moderate), BAI 32 (severe) and LSAS 111 (very severe). After two weeks of treatment, we obtained the following results: BDI 11 (minimal), BAI 6 (minimal) and LSAS 74 (moderate). At the end of treatment, we noted the following results: BDI 9 (minimal), BAI 5 (minimal) and LSAS 69 (moderate). On two weeks follow-up, we verified the following results: BDI 5 (minimal), BAI 1 (minimal) and LSAS 54 (moderate) (Fig. 2B).

Before rTMS treatment, patient presented very severe level of social anxiety, observed in LSAS, reporting for example, working while being observed, expressing a disagreement or disapproval to people you don’t know very well (areas most highly rated on LSAS; assessment point level 3). Two and four weeks after rTMS treatment and after 2 weeks follow-up, patient showed large reduction in social anxiety symptoms (areas most highly rated on LSAS; assessment point level 1- minimal) compared to baseline. With regard to BAI, patient presented severe level of anxiety in baseline, reporting for example, nervous, scared and sweating (areas most highly rated on BAI; assessment point level 3). Two and four weeks after rTMS treatment and after 2 weeks follow-up, patient showed large reduction in anxiety symptoms (areas most highly rated on BAI; assessment point level 0 - no anxiety) compared to baseline. At last, we observed in BDI that patient had moderate depressive symptoms in baseline, reporting for instance, I feel I am being punished, I have no appetite at all anymore (areas most highly rated on BDI; assessment point level 3). Two and four weeks after rTMS treatment and after 2 weeks follow-up, patient showed large reduction in depressive symptoms (areas most highly rated on BDI; assessment point level 0- no depression) compared to baseline.

We suggest that 1Hz rTMS over vmPFC (responsible for emotional regulation) [69], promoted neuromodulation treatment due to its focus on directly targeting the neural circuitry of the disorders. rTMS holds the potential to selectively modulate brain circuitries involved in pathological processes and shifts the perspective of treatment from changing the neurochemistry within the synapse, to altering or modulating the function of the neural circuitry in the brain that is believed to be disorganized in certain disorders [9,10]. Thus, it seems that the low-rTMS treatment improved the anxiety and depression levels and social skills performance in a more controlling and therapeutic manner. Despite our positive findings, without a placebo control, at this point these assumptions are merely speculative.

However, after an extensive analysis regarding the findings of rTMS for anxiety disorders [9,10] and based on the slightly observation related to the cases, we now hypothesize that a potential rTMS regime for treating SAD, would be use low-rTMS over the right mPFC and high-rTMS over the left mPFC, which would provoke an transcallosal stimulation of the right mPFC, in order to induce a balance in brain activity. The latter type of stimulation, i.e., high-rTMS, was used as an additional strategy to potentiate the effects of low-rTMS. In addition, the considerations regarding the protocols of depression according to which rTMS should be administered for at least 4 weeks on consecutive weekdays (i.e., 20 sessions) must be taken into account for achieving consistent therapeutic effects. Moreover, an effective control for antidepressant effects should be employed in such studies. This hypothesis raises the exciting possibility that a balanced TMS approach may be fruitful as a potential therapy for SAD.

CONCLUSION

Here, we firstly hypothesized that the application of low-rTMS over the right medial PFC (mPFC; the main structure involved in SAD circuitry) was a potential therapeutic option for SAD. However, after an extensive analysis regarding the findings of rTMS for anxiety disorders [9,10] and based on our findings, we now hypothesize that the application of low-rTMS over the right medial PFC (mPFC; the main structure involved in SAD circuitry) combined with high-rTMS over the left mPFC, for at least 4 weeks on consecutive weekdays, may induce a balance in brain activity, opening an attractive therapeutic option for the treatment of SAD.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

All authors designed, managed the literature searches and drafted most of the manuscript. Flávia Paes, Mauro Carta, Adriana Cardoso Silva, Sergio Machado and Antonio Egidio Nardi wrote the first draft of the manuscript. All authors contributed to and have approved the final manuscript.