All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Child and Adolescent Behavior Inventory (CABI): A New Instrument for Epidemiological Studies and Pre-Clinical Evaluation

Abstract

Background:

Some questionnaires have already been elaborated to collect information from parents of children and adolescents, both as preparation for clinical evaluation and for screening and epidemiological studies. Here a new questionnaire, the CABI, is proposed, and it is validated in a population of 8-10 year-old children. Compared to existing questionnaires, the CABI has been organized so as to be of medium length, with items concerning the most significant symptoms indicated by the DSM-IV-TR for the pertinent disorders, and covering a wider range than existing instruments. There is no charge for its use.

Methods:

The answers of the parents of 302 children in the last 3 years of primary school provided the normative data. A discriminant validation was done for internalizing and externalizing disorders and as a comparison with self-administered anxiety and depression scales. Exploratory factor analysis and internal consistency were also performed.

Results:

Distribution of scores on the main scales in the normal population shows positive skewness, with the most frequent score being zero. A highly discriminant capability was found in regard to the sample of children with internalizing and externalizing disorders, with high correlation with the self-administered anxiety and depression scales.

Conclusion:

The CABI appears to be capable, at least for 8-10 year-old children, of effectively discriminating those with pathological symptoms from those without. Compared with the widely- used CBCL, it has the advantages of a lower number of items, which should facilitate parental collaboration especially in epidemiological studies, and of being free of charge.

INTRODUCTION

In psychiatry, information from parents is relevant for the clinical evaluation of children and adolescents. Questionnaires are often used for this purpose, since, without being time-consuming for the psychiatrist, they can provide an initial series of data, to be further investigated in the clinical interview both with the parents and with the child/adolescent himself.

Moreover, this type of questionnaire may be used for screening and epidemiological studies, when information from a large number of subjects is collected and a face-to-face interview is not feasible.

Some questionnaires have already been elaborated for these purposes [1-4]. The most widely-used questionnaire to be completed by parents is the Child Behavior Checklist 6-18 (CBCL 6-18) [1], used in both epidemiological and clinical studies (more than 1380 citations in PubMed). However, its administration time is rather long (113 items), whichcould discourage parents from giving accurate responses, especially in epidemiological studies. Moreover, the construct validity of the syndrome dimensions of CBCL has been questioned [5]. It is covered by copyright and therefore represents an economic burden, especially in epidemiological studies.

Other questionnaires are similarly rather long and under copyright [3, 4] or too short to supply sufficient data for evaluating the subject [2].

This situation prompted one of the authors (CC) to construct a new questionnaire for parents, the Child and Adolescent Behavior Inventory (CABI), in order to provide a free and possibly valid alternative to the CBCL. This paper presents the new questionnaire (see APPENDIX), its first normative data in a population of children attending primary school, and its discriminant validity in internalizing and externalizing disorders.

The CABI (Child and Adolescent Behavior Inventory)

The questionnaire has been elaborated to be characterize by:

1-a series of items requesting information on a wide range of disorders, including those not covered by other questionnaires.

2-a moderate number of items, in order to facilitate the collaboration of the parents.

It was decided to let clinics and epidemiologists use the questionnaire free of charge, in order to favor clinical practice and research.

Construction

The moderate length of the CABI required the use of a limited number of items in reference to each psychopathological area explored. In order to obtain maximum information from these items, those most clinically relevant were chosen, taking in account as much as possible the descriptions stated in the “Diagnostic criteria” of the DSM-IV-TR [6].

A pilot study on a larger number of items (110) was carried out on 100 parents of children and adolescents, 74 from 5 classes of 3 different schools and 26 coming to the out-patients’ clinic for examination. After compilation of the questionnaire, a direct interview with the responding parents was carried out. All responses were checked, asking the parents the significance of each answer they had given and verifying actual correspondence with the behavior indicated by each item.

Successive selection of items was performed taking into account a) the frequency of misinterpretation of the meaning of the question; b) the equivalence of the items pertaining to the same group, having almost always had the same response.

The number of items was finally reduced to 75.

Description

The whole questionnaire is reported in the APPENDIX. The general layout follows DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria. However, due to the necessity of drastically reducing the number of items in order to facilitate easy administration, the most representative symptoms reported in the DSM-IV-TR diagnostic criteria were chosen; in some cases, exact correspondence with symptoms is lacking, since the items refer to more general symptoms, including those indicated in DSM-IV-TR.

The first items (nos.1 to 4) concern four types of symptoms which may be isolated but which are more frequently included in anxiety or depressive disorders. Anxiety disorders are evaluated according to the DSM-IV-R as generalized (3 items, nos. 5-7; items 5 and 6 on the variety of tension and of apprehension, plus 7 concerning school, relevant to children and adolescents), separation (1 item, no.8), social (2 items, nos.9 and 10), phobias (no.11). Obsessive-compulsive symptoms are explored by items nos.12-15. Then follow 2 items concerning the self-confidence (nos.16 and 17), which may be reduced in anxiety, obsessive-compulsive and depressive disorders. Finally, no. 18 inquires about the presence of post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD).

The 10 items exploring depressive symptoms ask about mood (items nos.19-22), lack of interest (no.23), self-esteem (no.24), aboulia (no.25), guilt (no.26) and suicidal thoughts and attempts (nos.27 and 28). Four items follow concerning irritability (nos. 29 to 32), which in children and adolescents can be associated with both a depressive and an externalizing disorder, particularly oppositional defiant and conduct disorders. The examiner can evaluate the real significance according to the associated symptoms.

Externalizing behavior of oppositional-defiant disorder (ODD) and conduct disorder (CD) is explored by 10 items (nos. 33 to 42). The following 9 items (nos.43-51) explore the hallmarks of the attention deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD): impulsivity nos.43-45, hyperactivity nos.46-48, and attention deficit nos.49-51. These items were chosen since they are very characteristic of and frequent in this disorder.

Four items (nos. 52-55) ask about the correct evaluation of reality, and 6 (nos. 56-61) social relationships. Two items (nos. 62 and 63) are dedicated to sphincter control, 4 (nos. 64-67) to eating problems, 2 (nos. 68 and 69) to sex, 3 (nos. 70-72) to smoking, alcohol and substance abuse, 2 (nos. 73 and 74) to school performance and finally no.75 to passive bullying.

Broader groups can be delineated: a) “internalizing disorders”, if viewed as anxiety and depression symptoms, could include items nos.5-10 and 19-28; however, in a broader sense, that category could include all the items from no.1 to no.28; b) “externalizing disorders” includes items nos. 33-42 and possibly nos. 29-32, while nos.43-51 are specific for ADHD, an externalizing disorder with peculiar characteristics.

All the psychopathological areas explored by the CBCL are also included in the items in CABI, which has in addition the following ones, lacking in the CBCL (the figure refers to the item number): 2.Hypocondria, 8.Separation anxiety, 15.Order-Compulsions, 16-17.Insecurity, 18.PTSD, 56-61. Difficulties in relationships (suggesting elements of a pervasive developmental disorder, PDD), 65-67.Anorexic disorder, 74.Deterioration (which may be only functional, due to emotional problems), 75.Bullism (passive).

Unlike the CBCL, CABI items referring to a specific area are placed close together. This is done to help parents more easily understand specific problems when responding to the questionnaire. Moreover, it gives the clinic a rapid, first-glance evaluation of the case, without time-consuming calculation of the results by means of a grid, as in CBCL. The same criterion has been used in the CSI-4 [3].

Items are easily interpreted by parents. Experience in the outpatients’ clinic shows that 80-90% of the data referred corresponds to what emerges in the following clinical interview. However, some parents tend to underestimate or also scotomize some symptoms in their children or adolescents, considering them normal.

Application

The questionnaire can be used in two ways:

- Preclinical (pre-visit), as a first opinion on the part of parents/caregivers regarding the problems of their children-adolescents, prior to the interview. The CABI is compiled in the waiting room, without taking up the psychiatrist’s time.

Parents are presented with a panorama of practically all possible problems of children/adolescents coming for a psychiatric visit. Although they may come for a single, apparently limited problem, for example enuresis or encopresis, parents/caregivers are asked to evaluate whether many other types of problematic child/adolescent behavior is present in the child. Parents frequently have to indicate some which they are less aware of and which they can indicate only in answer to a precise question. Child psychopathology, unlike that of adults, frequently has many facets, sometimes functionally less relevant and more fleeting, of which however the clinician should be aware.

From the clinician’s point of view, the CABI allows him/her to immediately have a multi-area panorama of the patient’s behavior, giving an initial indication of behavioral domains to be more deeply explored during the clinical interview. This is useful both when the clinician continues with an unstructured interview, or when he/she decides to use a detailed wide-range rating scale, like the K-SADS-PL [7], since the results of CABI give an initial orientation regarding which subscales should be used, thus saving time. Grouping the items in relation to the area they explore facilitates rapid evaluation of problems concerning that area. - As a screening instrument for behavioral problems in children-adolescents. In epidemiological studies, people are frequently unwilling to dedicate much time to compiling questionnaires. The CABI is relatively short, despite investigating a wider range of behavior than the CBCL, and thus is more easily accepted by parents/caregivers.

VALIDATION

Subjects

Parents of 318 primary school children (163 females, 155 males) aged 8-10 years were asked to respond to the CABI. Eleven primary schools in Cagliari and the surrounding area were involved. Schools were selected on the basis of their balanced distribution in the metropolitan areas in relation to the number of inhabitants and the general socio-economic status in those areas. This study was part of a study on the emotional conditions of students in Cagliari and its environs. Validation data were collected in the course of a study approved by the Ethics Committee of the Azienda Ospedaliero-Universitaria di Cagliari (University Hospital of Cagliari). The study was supported by grants from the Regione Autonoma Sardegna and the Fondazione Banco di Sardegna. Written informed consent was obtained from the schools and parents.

In addition, the CABI was responded to by the parents of 31 children 8-10 y.o. with internalizing disorders and 20 children 8-10 y.o. with externalizing ones, evaluated and diagnosed in our clinic, most as outpatients at the time of the first consultation.

Methodology

Parents for the most part completed the CABI at school, some at home. Both parents were asked to answer the questionnaires together. However, questionnaires compiled by a single parent were accepted as well.

Answers were not anonymous, since parents were informed that, if some problems emerged from the evaluation of the instruments administered, they would be advised and could obtain a free consultation with a neuropsychiatrist or psychologist.

Due to the tender age of the children examined, the version of CABI administered was reduced by a few items, that is nos. 40, 41, 42 concerning severe antisocial disorders, nos. 67 and 68 concerning sex, and 70, 71, 72 concerning smoke, alcohol and drug use.

Parents of the clinical sample completed the CABI in the hospital waiting room.

Data from each item answered on the questionnaires were transferred to an Excel file. Those with missing or double answers in the main psychopathological areas (those to be analyzed statistically) were eliminated.

Statistical analyses were performed using the SPSS program (SPSS Statistical Software).

Internal Consistency

Since the CABI refers to a wide spectrum of different psychopathological conditions, internal consistency was evaluated in relation to the broadest homogeneous psychopathological areas of internalizing (anxiety and depression) and externalizing disorders.

Test-retest evaluation was not possible.

Discriminant Validation

The results for normal children were compared with those having a psychopathology in order to evaluate the discriminant capability of the main CABI scales. Mann & Whitney Non-Parametric Test U was used. As stated in the paragraph “Subjects”, the clinical sample included 31 children 8-10 years old with internalizing disorders and 20 children 8-10 years old with externalizing disorders, clinically evaluated and diagnosed in our clinic.

Concurrent Validity

Comparison was also made with the results of a self-evaluation of internalizing symptoms by the children themselves. Children (n=284) responded to the scales on anxiety and depressive symptoms of the SAFA [8], a self-administration instrument widely used in Italy [9-13], including 6 separate scales (anxiety, depression, somatic, obsessive-compulsive, psychogenic alimentary, phobias). For ages 8 to 10 years, the scale SAFA/A (for anxiety) includes 42 items and SAFA/D (for depression) 48 items (more items are included for older subjects). The child should answer each item as “true”, “in between” or “false”. Items follow diagnostic DSM-IV criteria and are grouped in subscales: in SAFA/A: generalized anxiety, separation anxiety, social anxiety and school-related anxiety; in SAFA/D: depressed mood, anhedonia-lack of interest, irritable mood, inadequacy-low self-esteem, insecurity, guilt, desperation. A simulation scale is included, in order to evaluate the accuracy and trustworthiness of answers. The results obtained on the SAFA/A and /D were compared with those for anxiety and depression items on the CABI, using a non-parametric correlation test.

Factor Analysis

The extraction method of principal component analysis was used for exploratory factor analysis, followed by Varimax rotation with Kaiser normalization.

RESULTS

After excluding questionnaires with one or more missing data, we obtained a final normative sample regarding 302 children (153 females, 149 males), aged 8-10 years (mean age 8.8, SD 0.8).

Normative Values

Table 1 shows mean and SD values obtained in the normal population of 302 children 8-10 years old concerning the main scales of the CABI, both in the whole population and subdivided according to sex.

CABI Scores on 302 Children 8-10 Yrs Old: Mean Values ± Standard Deviations in Relation to the Different Symptomatological Groups

| Total Population (n=302) | CABI Scores |

|---|---|

| Internalizing symptoms (excluding OCD) | items nos. 5 to 10 & 19 to 28 |

| 4.4±3.7 | |

| Externalizing symptoms (excluding ADHD) | items nos.29 to 42 |

| 1.8±2.5 | |

| ADHD symptoms | items nos.43 to 51 |

| 3.5±3.7 | |

| OCD symptoms | items nos.12 to 15 |

| 0.4±0.7 | |

| Relationships symptoms | items nos.56 to 61 |

| 0.2±0.6 | |

| Females (n=153) | CABI scores |

| Internalizing symptoms (excluding OCD) | 4.5±3.7 |

| Externalizing symptoms (excluding ADHD) | 1.5±2.3 |

| ADHD symptoms | 2.7±2.9 |

| OCD symptoms | 0.4±0.7 |

| Relationships symptoms | 0.2±0.6 |

| Males (n= 149) | CABI scores |

| Internalizing symptoms (excluding OCD) | 4.4±3.7 |

| Externalizing symptoms (excluding ADHD) | 2.1±2.6 |

| ADHD symptoms | 4.3±4.2 |

| OCD symptoms | 0.3±0.7 |

| Relationships symptoms | 0.3±0.6 |

Discriminative Capability of CABI Main Scales in Relation to the Psychopathological Disorders they Investigate. Non- Parametric test of Mann & Whitney

| Normal (N=302) | Anxiety & Depressive Disorders (N=31) | U | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| CABI internal. 5-10 & 19-28 | 4.4±3.7 | 14.8±2.7 | .000 | .000 |

| ODD, CD, ADHD (N= 20) | ||||

| CABI external. 33-42 & 43-51 | 1.8±2.5 | 13.2±3.2 | .500 | .000 |

Correlations Between the Anxiety and Depression Scales of the SAFA and the CABI Scales Concerning Anxiety and Depression

| N=284 | SAFA Anxiety | SAFA Depression | |

|---|---|---|---|

| CABI anxiety | Spearman's rho= | .134 | -.010 |

| P= | .012 | .433 | |

| CABI–depression | Spearman's rho= | .214 | .108 |

| P= | .000 | .034 | |

| CABI–irritability | Spearman's rho= | .249 | .162 |

| P= | .000 | .003 |

Exploratory Factor Analysis (Extraction Method: Principal Component Analysis; Rotation Method: Varimax with Kaiser Normalization)

| Items no. | Factors | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 2 | 3 | |

| 05 | .017 | .249 | .553 |

| 06 | .036 | .035 | .726 |

| 07 | -.018 | -.013 | .589 |

| 08 | .131 | -.038 | .280 |

| 09 | -.074 | .022 | .582 |

| 10 | .004 | .007 | .507 |

| 11 | .101 | .032 | .361 |

| 16 | .083 | .102 | .626 |

| 19 | .162 | .260 | .278 |

| 20 | -.029 | .574 | .230 |

| 21 | -.039 | .572 | .141 |

| 22 | .034 | .329 | .348 |

| 23 | .181 | .464 | .095 |

| 24 | .183 | .263 | .498 |

| 25 | .241 | .348 | .319 |

| 26 | -.038 | .326 | .342 |

| 29 | .233 | .691 | -.003 |

| 30 | .231 | .688 | -.025 |

| 31 | .116 | .622 | .085 |

| 32 | .125 | .684 | .099 |

| 33 | .615 | .297 | -.034 |

| 34 | .665 | .284 | .000 |

| 36 | .612 | .373 | -.058 |

| 37 | .256 | .458 | -.096 |

| 38 | .510 | .108 | -.021 |

| 39 | .157 | .077 | .168 |

| 43 | .638 | .332 | .013 |

| 44 | .595 | .166 | -.110 |

| 45 | .673 | .102 | .205 |

| 46 | .747 | -.118 | .064 |

| 47 | .804 | -.084 | .062 |

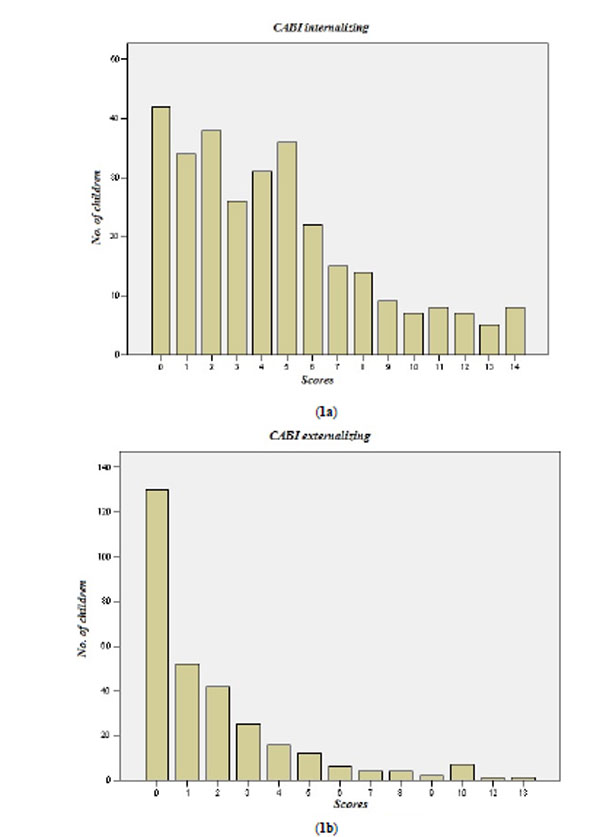

Distribution of the results concerning the main psychopathological areas are shown in Fig. (1a) (internalizing) and (1b) (externalizing). All curves have positive skewness, with higher frequency of the lowest scores and presence of a limited number of subjects having scores beyond the 2 standard deviations.

Internal Consistency

Cronbach’s alpha index for the Internalizing Scale (restricted scale: items nos.5-10 and 19-28) was 0.822. For the Externalizing Scale (items nos.29-42), alpha was 0.871. For the group of ADHD symptoms (items nos. 43-51), alpha was 0.873. All values are higher than 0.800, therefore qualifying as “good”.

Discriminant Validation

Results are shown in Table 2. There is a highly significant difference in the scores of children with internalizing and externalizing pathology as compared to normal ones (U test, P .000).

Concurrent Validity

Table 3 shows the results of correlations between answers by parents to the CABI items on “anxiety” areas (nos. 5-10), “depression” (nos.19-28) and “irritability” (nos. 29-32) and the responses of their children to the Anxiety and Depression scales of the SAFA. The CABI and SAFA correlate very well for most parameters; surprisingly, CABI depression and irritability items show higher correlation with SAFA anxiety than with SAFA depression.

Factor Analysis

Data of factor analysis are shown in Table 4. Exploratory factor analysis was performed on the group of 302 normal children. For the CABI, the items on anxiety (5-10), depression (19-28), irritability (29-32), externalizing (33-39) and ADHD (43-51) were selected; moreover, items nos.11 (fears) and 16 (insecurity) were included.

Analysis (Table 4) shows differentiation in 3 factors, the best obtained. Factor 1 includes ADHD and externalizing items of ODD type, with the exception of nos.37 (“He quarrels frequently”, fitting well with factor 2) and 39 (“He often hits people”, fitting better with factor 3, although with a minimal score difference with respect to factor 1). Factor 2 includes half of the items of depression (nos.20, 21, 23 and 25) and all the items of “irritability” (nos. 29-32), with the other half of the depression items (nos.19, 22, 24, 26) fitting well with factor 3. This latter factor includes all the anxiety items.

DISCUSSION

The new instrument CABI appears to be highly capable of differentiating children with pathological symptoms from those without them, at least for the age range examined and for the most relevant and diffuse types of pathologies, that is internalizing (anxious and depressive type) and externalizing (oppositive-defiant, rule-breaking, aggressive and ADHD) disorders. The evaluation of anxiety and depression symptoms by parents using the CABI correlates with the responses of their children on the self-administered scale for anxiety and depression of the SAFA battery. Although in general the evaluation by parents of their children’s conditions tends to differ from the evaluation by the latter, the correlation with the SAFA suggests a further capability of the CABI to clearly indicate the suffering of children in these areas.

The factorial distribution of items on the CABI appears quite coherent with their theoretical distribution. A still more coherent distribution would surely be obtained in a population of children with pathologies.

In this study, statistical evaluation was carried out for the main psychopathological areas explored. An insufficient number of patients in minor areas of psychopathology did not consent their evaluation. However, our experience with individual cases suggests that answers by parents give at least a minimal signal of some problems in those areas, and this is sufficient to indicate to the psychiatrist the necessity of further exploration of that area. On the contrary, there is a frequent tendency to over-indicate symptoms, at least by parents bringing their children for examination; in this case, the subsequent clinical interview will clarify the exactness of what was reported.

Although having a limited number of items in general and for each of the main areas explored, perhaps bringing with it a risk of lower reliability [14], the CABI has items based as much as possible on the diagnostic criteria of the DSM-IV-TR. The stringent selection of items, according to the main symptoms of the pathological areas to be evaluated, permits a sufficiently accurate and reliable exploration of behavioral manifestations pertaining to those areas.

On the other hand, it should be noted that a longer scale would not necessarily provide more information on the aspects of the psychopathology explored, if several items are not sufficiently informative. For example, the longer CBCL has several items not strictly or clearly referring to psychopathological manifestations (e.g. nos. 1, 6, 12, 19, 44, 58, 62, 63, 64, 69, 76, 77, 80, 92, 109): therefore they do not add significant explorative elements to the instrument.

It seems more useful to permit parents to concentrate on a few more informative items, as in the CABI. In particular, in the use of a questionnaire for epidemiological and screening studies, this is quite relevant, due to the fact that parents are less motivated to cooperate (this consideration is even more valid for questionnaires to be compiled by teachers). Systematic screening at the school level of emotional and behavioral disorders to facilitate early detection of problems, especially those of the less evident internalizing disorders, is probably one of the most relevant possibilities for preventing more serious disorders at a later age.

The grouping of items according to the psychopathological area explored facilitates case evaluation by the psychiatrist when the CABI is used as a preparatory instrument to clinical examination.

Data show that this is valid for the limited age-band of the population we examined. A study is in progress to evaluate other age-bands of children and adolescents.

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN

A few questionnaires exist for use in child and adolescent psychiatry, asking parents information on their children. They are used both in preparing or completing the clinical evaluation, and for screening and epidemiological purposes. Three of them have a large number of items and are not free of charge. The 4th is very short, and explores a limited number of psychopathological areas.

WHAT THIS PAPER ADDS

A new questionnaire (CABI) is proposed and validated in a population of children 8-10 years old.

The CABI appears capable of differentiating children with internalizing and externalizing symptoms from those without them. Compared with widely-used instruments like the CBCL, the CABI has the advantage of a smaller number of items, the presence of some items exploring symptoms not explored by the CBCL and of being free of charge.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The authors confirm that this article content has no conflicts of interest.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

A grant from the Regione Autonoma della Sardegna (Autonomous Region of Sardinia) and the Fondazione Banco di Sardegna (Sardinian Bank Foundation) made possible the administration of the scales to school children.

APPENDIX

The CABI questionnaire for parents is reported here in the form in which it can be administered. It is free of charge and can be photocopied. An Italian version will be provided by the author on request (cianchet@unica.it).

Those using it extensively are invited to make a donation to UNICEF.

C.A.B.I.

QUESTIONNAIRE FOR PARENTS

By Carlo Cianchetti M.D., University of Cagliari, Italy

| Name of child or youth:______________________________________________________________________ Sex: M□ F□ Date of birth:_______/_______/_____ Age:__________ Class:_________ Date of compilation:_____/____/_____ Compiler: mother (name)___________________________________father (name)__________________________________________ |

Instructions

The following statements refer to problems which may be present in children/youth. Please answer as regards your child and what has taken place during the last six months. For each statement, ask yourself if the situation is very true, somewhat or sometimes true, or not true. Answer by marking an “X” in the appropriate square. Some questions may not apply to your son or daughter if he/she is very young, as the questionnaire also regards adolescents; however, please answer all the questions. If the meaning of one or more questions in unclear to you, or you are unable to answer, immediately note the number of the question/s at the bottom of the questionnaire and when you hand it in, ask for explanations.

| Very True | Somewhat or Sometimes True | Not True | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | Your son/daughter often complains about some physical discomfort (for example: a headache, stomach ache, etc.) | □ | □ | □ |

| 2 | He is excessively worried about illnesses and/or that he will get ill | □ | □ | □ |

| 3 | He finds it difficult to fall asleep or says he does not sleep well | □ | □ | □ |

| 4 | His sleep is disturbed by nightmares or waking up during the night | □ | □ | □ |

| 5 | He appears tense and/or anxious | □ | □ | □ |

| 6 | He tends to worry about everything | □ | □ | □ |

| 7 | He worries about school too much | □ | □ | □ |

| 8 | It is hard for him to be separated or far from his parents | □ | □ | □ |

| 9 | He is excessively shy | □ | □ | □ |

| 10 | He is usually embarrassed around strangers or people he does not know very well | □ | □ | □ |

| 11 | He is excessively afraid of something (e.g. the dark, being alone, insects, thieves) Specify what he is afraid of | □ | □ | □ |

| 12 | He is excessively afraid of dirt, so he has to wash continually | □ | □ | □ |

| 13 | There are repetitive actions

or “rituals” that he frequently repeats and he says he cannot help

doing them, If yes, describe which ones |

□ | □ | □ |

| 14 | He has an obsessive need for things to be in a precise order | □ | □ | □ |

| 15 | He is obsessed by unpleasant thoughts and cannot free himself from them | □ | □ | □ |

| 16 | He is very afraid of making mistakes | □ | □ | □ |

| 17 | It is hard for him to make decisions, even about unimportant things | □ | □ | □ |

| 18 | Has he ever been involved in

or witnessed particularly stressful events, after which his

behaviour changed in some way? If true, indicate what behavioural changes occurred after the event |

□ | □ | □ |

| 19 | He cries for no reason or about unimportant things | □ | □ | □ |

| 20 | He often seems sad | □ | □ | □ |

| 21 | He is often in a black mood (“depressed”) | □ | □ | □ |

| 22 | He says or shows that he is not happy | □ | □ | □ |

| 23 | He shows no interest, not even in pleasant things | □ | □ | □ |

| 24 | He feels inferior to others; he has low self-esteem | □ | □ | □ |

| 25 | He is often tired or listless; everything exhausts him | □ | □ | □ |

| 26 | He blames himself too much | □ | □ | □ |

| 27 | He has sometimes said he does not want to live any longer | □ | □ | □ |

| 28 | He has hurt himself or tried to hurt himself | □ | □ | □ |

| 29 | He is very irritable | □ | □ | □ |

| 30 | He often gets angry, even about unimportant things | □ | □ | □ |

| 31 | He has frequent mood changes | □ | □ | □ |

| 32 | He is quick-tempered and has fits of anger | □ | □ | □ |

| 33 | He does not obey and it is difficult to make him obey | □ | □ | □ |

| 34 | He does not follow the rules | □ | □ | □ |

| 35 | He often tells lies or cheats | □ | □ | □ |

| 36 | He is domineering and always wants to assert himself | □ | □ | □ |

| 37 | He quarrels frequently | □ | □ | □ |

| 38 | He bothers and intentionally annoys others | □ | □ | □ |

| 39 | He often hits people | □ | □ | □ |

| 40 | He destroys things | □ | □ | □ |

| 41 | He is or has been cruel to animals or people | □ | □ | □ |

| 42 | He has committed petty theft | □ | □ | □ |

| 43 | He is impulsive and acts before thinking | □ | □ | □ |

| 44 | He tends not to take turns when he is playing | □ | □ | □ |

| 45 | He interrupts, disturbing games or others’ conversations | □ | □ | □ |

| 46 | He is always moving around and cannot stay still | □ | □ | □ |

| 47 | He cannot sit down for a long time but has to get up | □ | □ | □ |

| 48 | He runs and jumps everywhere in an exaggerated way | □ | □ | □ |

| 49 | He has trouble concentrating while doing his homework | □ | □ | □ |

| 50 | He has trouble paying attention to something for a long period | □ | □ | □ |

| 51 | He gets tired very quickly even when he is playing | □ | □ | □ |

| 52 | He feels persecuted | □ | □ | □ |

| 53 | He is overly suspicious | □ | □ | □ |

| 54 | Sometimes he has strange ideas | □ | □ | □ |

| 55 | Sometimes he says he sees or hears things that are not there | □ | □ | □ |

| 56 | He has difficulty in relating to and interacting with others | □ | □ | □ |

| 57 | He cannot make real friends or does not seem interested in doing so | □ | □ | □ |

| 58 | He does not play willingly with his peers | □ | □ | □ |

| 59 | He does not seem to express emotions using appropriate facial expressions | □ | □ | □ |

| 60 | His behaviour is "strange", unlike that of his peers | □ | □ | □ |

| 61 | He asks inappropriate questions, like overly-personal questions to strangers at inopportune times | □ | □ | □ |

| 62 | He sometimes wets the bed | □ | □ | □ |

| 63 | He sometimes dirties his pants during the day | □ | □ | □ |

| 64 | He stuffs himself with food | □ | □ | □ |

| 65 | He keeps to a strict diet (not prescribed by a doctor or dietician) | □ | □ | □ |

| 66 | He feels too fat or says that parts of his body are too fat | □ | □ | □ |

| 67 | He has recently lost a lot of weight | □ | □ | □ |

| 68 | He appears to be overly interested in sex | □ | □ | □ |

| 69 | He shows he would like to be of the opposite sex | □ | □ | □ |

| 70 | He smokes | □ | □ | □ |

| 71 | He drinks alcohol | □ | □ | □ |

| 72 | He uses drugs (smokes hashish or other dangerous substances) | □ | □ | □ |

| 73 | He does not do well at school | □ | □ | □ |

| 74 | He has recently done much worse at school | □ | □ | □ |

| 75 | His classmates or other children make fun of him, threaten or mistreat him | □ | □ | □ |

List the numbers of the questions whose meaning was unclear:...................... ................ ................ ................ ................ ............................................................

Does your child exhibit behaviour which seems to you different from that of his peers? Give details. ...................................................................................................................... ................ ................ ................ ................ ................................................................. ...........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................

Does your child exhibit behaviour which worries you? Give details.................................................................. ................ ................ ................ ................ .......... ........................................................................................................................................................................................................................................................... .......................................................... ........................................................ ........................................................ ...............................................................................

If there are episodes that worry you, it is better not to ignore them. Problems can usually be solved if they are faced adequately and in time. Problems that are ignored may later be difficult to solve.