All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Formal and Informal Help-Seeking for Mental Health Problems. A Survey of Preferences of Italian Students

Abstract

Help-seeking preferences for mental health are a crucial aspect to design strategies to support adolescents in an emotionally delicate life phase. Informal help-seeking is usually preferred but little was published about preferences in different cultures, and it is not clear whether informal and formal help are mutually exclusive or whether they are part of the same overall propensity to help-seeking. In a survey of 710 students in Milan, Italy, help-seeking propensity measured through an Italian version of the General Help-Seeking Questionnaire was high, similar in males and females (mean total score 3.8, DS 0.9); few (9%) tended not to seek help. The most-preferred source of help was a friend, then father or mother, partner, psychologist and psychiatrist. 355 students (55%) reported high propensity to seek both informal and formal help; 33 (5%) would only seek formal help. Help-seeking should be promoted in itself, rather than indicating professionals and professional settings as primary sources of help.

INTRODUCTION

Young people find themselves in a difficult condition with respect to help-seeking for mental health problems. They are dependent on adults, but at the same time seek independence and do not want their parents to know about their problems [1]; they often experience aversive emotions like anxiety, fear, or shame, but at same time lack emotional competence [2, 3]. They do not know exactly where to seek help, and this may discourage them from seeking help at all [4]. Adolescence is a stage in life when mental health problems can arise, but, despite the enormous impact problems in adolescence can have later in life [5], services do not seem adequately designed to meet this need [6, 7]. Help-seeking attitudes are therefore the outcome of a more complex view of mental health, relationships with peers and with the family in the process of identity-building.

Despite some inconsistencies in research findings, certain patterns of help-seeking preferences and behaviour are generally reported in the literature. Young people tend not to seek help from professional sources [8]. Among informal sources, family and friends are the most important [3, 9]. Females are more likely to seek help than males, who tend more to rely on themselves to solve their problems, often denying the presence of a mental problem [3, 10].

With few exceptions [7], most research has been done in English-speaking countries, and we know little about help-seeking preferences in cultures where family relationships may be different. Moreover, although young people consistently prefer informal help in most studies, it is not clear whether the two sources are mutually exclusive or whether they are manifestations of the same overall propensity to help-seeking.

To encourage young people to help-seeking, Progetto Itaca, a no-profit association active in Milan, Italy, in the field of prevention of mental disorders, has been running schemes in schools on stigma and self-stigma, and mental health literacy since 2001. The interventions normally consist of two sessions in each class with presentations and interactive moments. The focus is on risk factors for mental disorders, their signs and manifestations, and paths to care, trying to mix information and explanations from volunteer psychiatrists and questions and observations from the students as much as possible.

In 2008 the intervention was also examined for its effect on mental health literacy and help-seeking preferences through self-administered questionnaires (at baseline, post-intervention and three-month follow-up), one concerning attitudes and knowledge on mental health, and the other help-seeking preferences. This paper deals only with the help-seeking preferences of young people before they were exposed to the intervention.

METHODS

The questionnaire was developed ad hoc starting from the General Help-Seeking Questionnaire by Rickwood, Deane, Wilson and Ciarrochi [3, 8], and investigated attitudes towards asking for help from ten people. The Italian version was slightly modified in number, types and order of people to whom the students might go for help, which became: father or mother, clergyman, psychiatrist, nobody, friend, other relative, psychologist, general practitioner, help-line, partner, teacher, other.

The starting question was: “Here is a list of people who you might ask for help in case of psychological difficulty. Should you realize you feel mentally poorly, would you go to them for help or advice?”. Score 1 meant “Surely yes” and 7 “Surely not”, score 4 meant “I don’t know”. The reliability of the questionnaire was evaluated on a sample of 30 students in the same grade as the study sample with a test-retest method, administering the questionnaire twice with a two-week interval. A weighted kappa index was computed for each item. Reliability values ranged from 0.47 to 0.74, with the exception of the item 10, boyfriend or girlfriend, that performed a kappa value of 0.37. Such a low value can be considered a paradoxical underestimation of an higher agreement due to the asymmetric balance of data distribution, as described by Feinstein and Cicchetti [11]. The wording of the item was kept as it was.

Ten schools in Milan were contacted, and seven agreed to participate. They were large schools in central areas of Milan: one was a technical school, one a scientific high school, two were grammar schools, and three were schools oriented to education and social work. The study was planned for grade eleven, where the students are usually 16 years old. The total number of students enrolled in the classes was 897, 328 (36.6%) were males and 569 (63.4%) females. In the first week of December 2008 the questionnaire was given to all the classes, one month before the intervention was scheduled, in order to avoid any influence on students’ answers reflecting the ideas and values presented by the intervention. Nine Progetto Itaca volunteers proposed the study to the teacher “responsible for health issues” in each school. Eight hundred students were present on that day and were given the questionnaires in their own classroom with the collaboration of a teacher. The investigation took place on three different days in the first week of December 2008.

We created a global help-seeking score, obtained from the means of the 12 items, with lower scores meaning more propensity to ask for help [8]. We computed Cronbach’s Alpha to test the internal consistency of the scale, obtaining a score of 0.55. Cronbach Alpha indexes were computed for each variable to test the internal consistency, and values ranged from 0.56 for the close informal help group to 0.69 for the formal help group.

The ten possible sources of help were divided into three groups: formal help, close informal help, and broad informal help. The formal help group included a psychiatrist, psychologist, and general practitioner; the close informal help group a boyfriend or girlfriend, friend, father or mother, other relative. Teacher, clergyman and help-line were grouped with the close informal help into the wider group of broad informal help.

In order to assess whether those with propensity to informal help also had propensity to formal help and viceversa, we computed two variables according to the highest score in one of three possible sources of formal and informal help: for instance, value 1 in formal help corresponded to having score 1 in one or more formal sources of help, value 6 to having scores equal or higher than 6 in the three sources. For this analysis the three people included in informal help were father or mother, friend, boyfriend or girlfriend. The two variables were then crosstabulated.

Descriptive statistics were computed for every single item and for the different scales. Categorical variables were compared using the Chi-square statistics (χ2), and the Wilcoxon test was used for continuous non-parametric variables such as global help-seeking.

All analyses were done using SAS version 9.1.

All students of the grade involved and their parents were informed of the study and that they were free to refuse.

RESULTS

The questionnaires were distributed to 800 students who were at school on that day. A total of 90 students did not complete the questionnaires; of the 710 completed, 672 were considered valid, and 424 (63,1%) of them were from females. Those who said they would not seek help from anybody were 60 (9%). The person the students were most likely to ask for help was a friend, followed by father or mother, partner, then psychologist and psychiatrist. The lowest preferences were given to clergymen and help-line (Table 1). Males and females showed very similar scores, with the only slight but statistically significant differences found for friend and psychologist, who were preferred more by female students.

Means and Standard Deviations (SD) of propensity scores and percentages of students in the highest (scores 1 and 2) and lowest (6 and 7) propensity categories for 12 sources of help. Milan, Italy 2008

| Mean (SD) | Score 1 or 2 (yes) No. (%) | Score 6 or 7 (no) No. (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| friend | 2.1 (1.4) | 461 (71.1) | 31 (4.8) |

| father or mother | 2.4 (1.8) | 425 (65.6) | 67 (10.3) |

| boyfriend/girlfriend | 2.5 (1.8) | 411 (63.4) | 72 (11.1) |

| psychologist | 2.9 (1.8) | 327 (50.5) | 75 (11.6) |

| psychiatrist | 3.5 (1.9) | 229 (35.3) | 121 (18.6) |

| other relative | 3.7 (2.0) | 211 (32.6) | 159 (24.5) |

| general practitioner | 4.5 (1.9) | 110 (17.0) | 232 (35.8) |

| someone else | 4.9 (1.8) | 56 (8.6) | 269 (41.5) |

| teacher | 5.2 (1.8) | 58 (8.9) | 340 (52.5) |

| help-line | 5.5 (1.8) | 60 (9.3) | 409 (63.1) |

| nobody | 5.7 (1.8) | 60 (9.3) | 441 (68.0) |

| clergy | 5.8 (1.7) | 43 (6.6) | 455 (70.2) |

Mean (and SD) help-seeking scores. Milan, Italy 2008

| Mean (SD) | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Overall | Males | Females | |

| Overall help-seeking | 3.78 (0.86) | 3.81 (0.88) | 3.76 (0.85) |

| Formal help-seeking | 3.63 (1.46) | 3.66 (1.51) | 3.62 (1.44) |

| Close informal help-seeking | 2.68 (1.17) | 2.71 (1.13) | 2.66 (1.19) |

| Broad informal help-seeking | 4.10 (0.95) | 4.10 (0.95) | 4.10 (0.95) |

The mean total score was 3.8 (DS 0.9). Propensity was higher for close informal help (2.7, DS 1.2) than formal help (3.6, DS 1.5) (Table 2). For broad informal help (i.e., including also teacher, clergyman and help-line), the relationship was reversed, with broad informal help-seeking scoring higher (i.e. less propensity) (4.1 overall) than formal.

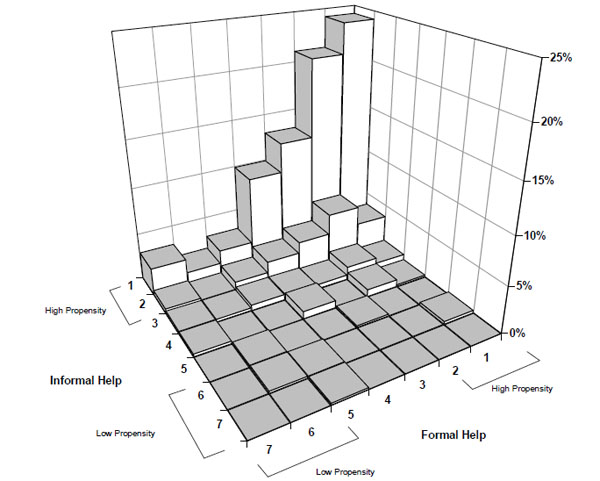

A total of 355 subjects (55%) showed high propensity (score 1 or 2 in at least one source of help out of the three selected) to both informal and formal help; those who showed high propensity to informal help and low to formal help were 33 subjects (5%), and 2 had little propensity to informal help and high to formal help (Fig. 1).

Distribution of students according to propensity to formal and informal help-seeking. Milan, Italy 2008.

DISCUSSION

Help-seeking for emotional problems was accepted and considered a viable option in case of emotional and psychological difficulties. The majority of students reported they tended to seek help in case of serious difficulties, with only a small minority not willing to seek any type of help. Preferences were not strictly divided into formal and informal help, suggesting that help-seeking is a general attitude.

The students tended to prefer close sources of help, namely a friend, father or mother, or partner, but the fourth most preferred source of help was a psychologist, indicating that professional help was considered an important source by about half the students.

The clergyman, help-line and teacher were substantially excluded by students’ help-seeking preferences. A recent study gave similar findings, with the highest preferences for mothers and friends, then siblings and fathers, and the lowest preferences for teacher, clergy, school counsellor, school nurse, pastoral support and help-line [9]. General practitioners were also identified as a source of help by less than 1 out of 5 of the students, in agreement with Leavey et al. [9].

In agreement with other indications [12], psychologist was preferred to a psychiatrist. If the psychologist is seen as the person who puts communication and talking at the centre of the relationship more than the psychiatrist, this indicates that a medically specialised approach is less appealing for young people, and give clues for designing prevention and information campaign in mental health.

We observed no differences between males and females, whereas others found that females tended to seek help more than males, although with changing patterns across age [3]. When we analysed the propensity to seek help from specific people in the two sexes, we found that females preferred talking more.

Though close informal help is its leading component, help-seeking should be promoted as a general attitude. Professional help is trusted if young people know what trust in people in general means and if they are aware of their feelings and can handle and communicate them [3, 13]. Therefore, indicating professional help as the real or best source of help can prove counterproductive. On the other hand, professional help needs to be publicized, and made more accessible to everyone and everywhere when needed. Professional help and reliable information about it should be more readily accessible in schools and other settings for the young [14].

The higher propensity to informal help can be related to the effect observed by Holzinger et al. [12] of the distinction between depressive symptoms and illness made by the lay public, and the lower propensity to recommend professional help when depressive symptoms occur in the context of adverse life events or in absence of a mental illness. If in the current study “feeling mentally poor” and “psychological difficulty” were interpreted as not having an illness, this might have produced a greater preference for informal help-seeking.

Propensity to formal help was however high. There are indications that the emphasis on the biological nature of the mental illness parallels greater acceptance of professional treatment [15], and this trend may be reflected in the good propensity observed in this Italian sample.

There are several limitations to this study. The questionnaire was only moderately reliable, possibly because the wording of the items was unclear. Distinguishing between mother and father would have been useful. Leavey et al. [9] found mothers were preferred to fathers.

When adapting the questionnaire to the Italian population we did not look for young people’s representatives’ opinions to improve the validity and the strength of the tool. This may be a major concern, since important options may have been overlooked. For instance, we did not include the Internet.

We do not know how generalizable these findings are. Since the schools were all in affluent or fairly affluent areas of Milan, which is a large city in the most productive region of Italy, these findings might not be confirmed in economically and socially less privileged areas, or in rural areas [16, 17]. More differences, for instance, might emerge between sexes. Questions to young people who left school after the compulsory years might give different results, and data on that are needed. The 11% of refusals might in part come from students with less propensity to help-seeking, although this would not substantially modify the findings. It is however unlikely that any important bias occurred, since the distribution of males and females who gave valid answers overlapped with that of the original sample.

Social class and ethnicity were not investigated. However, variability in ethnicity was extremely limited in the schools were the intervention took place, with the large majority of pupils being born in Italy and from Italian families. We know that some differences in social class can be associated with schools, with the scientific and grammar schools attracting students from upper classes, but we did not observe any significant differences across schools.

Moreover, our questionnaire only investigated the types of help-source, and not the other two components identified as essential for a thorough measurement of help-seeking, i.e. time context – addressing changes across past and recent behaviour and future intentions, and type of problem – addressing people’s levels of competence about who can be most helpful for specific problems [3].

Attitudes and preferences in help-seeking are not actual behaviour, which may be influenced by various factors, not taken into account in this investigation of preferences. Relying only on preference figures can be misleading, and the indications based on such data should be integrated with those of behaviour.

We do not know how formal and close informal help are related. It would be interesting to see whether formal help is contemplated after having talked to closer people, and whether, in case of serious disorders and need for professional help, friends and parents facilitate rather than hinder referral to an expert. The large overlapping of the two preference categories in this study suggests that the two go together and, although a very close source of help was preferred the most, formal help was also valued. The very limited variability in the distribution of the scores of propensity prevented more specific analyses.

CONCLUSION

The attitude to help-seeking in this Italian sample is similar to that observed in other social and cultural contexts, with a main role of informal sources of help. Formal help is however well accepted and the two types of help are not seen as mutually exclusive. Since friends and parents are the first sources of help when a young person feels unwell, emotional competence, awareness of feelings and psychological processes should be widespread common personal and cultural assets. Professional help is easier to look for and more effective when people seeking help are aware of their needs and motivated to be active in search of tools to answer their problems. More research is needed of: 1. how informal and formal help-seeking influence each other; 2. real help-seeking behaviour; 3. preferences and behaviour of young people who left school, and according to social class and ethnicity.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was conducted thanks to a grant from Progetto Itaca, and thank to the voluntary work of Mrs. Roberta Artom, Stefania Ciffani, Carola Colombo, Francesca Dubini, Francesca Fiocchi, Nicoletta Frangi, Carmela Radice Fossati, Lella Valsecchi, and Drs. Maria Cristina Cavallini, Margherita Comazzi, Stefano Erzegovesi, Roberto Garini, Gian Marco Giobbio, Giorgio Leonardi, Carmen Mellado.