All published articles of this journal are available on ScienceDirect.

Broadening of Generalized Anxiety Disorders Definition Does not Affect the Response to Psychiatric Care: Findings from the Observational ADAN Study

Abstract

Objective:

To elucidate the consequences of broadening DSM-IV criteria for generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), we examined prospectively the evolution of GAD symptoms in two groups of patients; one group diagnosed according to DSM-IV criteria and the other, according to broader criteria.

Method:

Multicentre, prospective and observational study conducted on outpatient psychiatric clinics. Patients were selected from October 2007 to January 2009 and diagnosed with GAD according to DSM-IV criteria (DSM-IV group) or broader criteria. Broader criteria were considered 1-month of excessive or non-excessive worry and only 2 of the associated symptoms listed on DSM-IV for GAD diagnosis. Socio-demographic data, medical history and functional outcome measures were collected three times during a 6-month period.

Results:

3,549 patients were systematically recruited; 1,815 patients in DSM-IV group (DG) and 1,264 in broad group (BG); 453 patients did not fulfil inclusion criteria and were excluded. Most patients (87.9% in DG, 82.0% in BG) were currently following pharmacological therapies (mainly benzodiazepines) to manage their anxiety symptoms. The changes observed during the study were: 49.0% and 58.0%, respectively of patients without anxiety symptoms as per HAM-A scale at the 6 month visit (p=0.261) and 59.7% and 67.7%, respectively (p=0.103) of responder rates (> 50% reduction of baseline scoring).

Conclusion:

Broadening of GAD criteria does not seem to affect psychiatric care results in subjects with GAD, is able to identify the core symptoms of the disease according to the DSM-IV criteria and could lead to an earlier diagnosis.

INTRODUCTION

Generalized anxiety disorder (GAD) is a chronic disorder mainly characterized by pathological worry. GAD also presents with a variety of somatic and psychological symptoms such as restlessness, muscle tension, sleep disturbance, irritability, difficulty concentrating, and fatigue [1]. GAD is one of the most prevalent anxiety disorders, with its lifetime prevalence estimated to be of 5.7% in the United States and 2.8% in Europe [2, 3]. Patients with GAD have a higher likelihood of developing other mood disorders in their lifetime; one of the most common is major depressive disorder, present in 62% of GAD patients [4]. Since GAD affects normal functioning, these patients are usually frequent users of healthcare resources; in fact, studies aimed to explore GAD clinical prevalence have estimated it to be 7.3% in primary care and up to 13% in the psychiatric outpatient setting [5, 6].

GAD is difficult to diagnose by primary care physicians and psychiatrists. In people who suffer GAD, commonly occurring comorbid conditions (e.g., depression, alcoholism, other anxiety disorders) often mask the underlying anxiety and result in a missed diagnosis of GAD [7, 8]. Other factors complicating the diagnosis of GAD are patients’ tendency to complain about the somatic symptoms, such as sleeplessness and fatigue, rather than the psychic symptoms (e.g., nervousness, apprehension, chronic worry) [9], and physicians’ lack of education in the diagnosis of GAD [10]. Diagnostic criteria have been modified in each edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) [1, 11, 12]. “Duration of excessive worry” criterion and the number of associated symptoms are still questioned today. The duration criterion was increased to 6 month in the DSM-III-R [12] to distinguish GAD from adjustment disorders or situational stress reactions. However, recent studies have suggested that this duration excludes significantly impaired patients from diagnosis [13]. DSM-V, which is expected to get released in May 2013, will revise the wording and organization of GAD diagnostic criteria in order to simplify them [14].

Meanwhile, several groups are conducting studies aiming to assess the need for 6 months duration of excessive anxiety and worry criterion [13, 15-17].

Using data from the US National Comorbidity Survey Replication, Ruscio et al. have demonstrated that broadening the GAD diagnosis criteria, more than doubles its prevalence [16]. This broadening of the criteria consists on a shortening of anxiety duration from “at least 6 months” to “at least 1 month (but less than 6 months)”, relaxing excessiveness to include excessive and non-excessive worry, and reducing the associated symptoms from a minimum of 3 to a minimum of 2. Most of the increase in prevalence comes from reducing the minimum duration to 1 month and, to a lesser extent, from eliminating the excessive worry requirement. Prevalence is minimally affected by requiring 2 rather than 3 associated symptoms. In a recent study conducted both in developed and developing countries, the 6-month duration criterion was not found to influence symptom severity, age of onset, persistence, impairment or comorbidity when compared to shorter criterion durations (1-2 months and 3-5 months) [15]. To our knowledge, there is no study aimed to evaluate prospectively the evolution of anxiety symptoms in patients diagnosed with broad DSM-IV criteria under medical practice. Before considering changing DSM-IV criteria, full consequences of these changes should be explored.

Broadening of GAD criteria could lead to earlier diagnosis of GAD patients and to diagnosis of otherwise under diagnosed patients. Earlier diagnosis could translate into a sooner start of treatment and this could lead to an improvement in the course of the illness and the quality of life. In fact, GAD patients have reported lower perceived quality of life than non-anxious controls and a lower degree of social functioning than patients with arthritis or diabetes [18]. In a recent study by Lee et al. [15], those patients with more than 12 months duration of symptoms were more severely impaired and had a lower rate of recovery than the groups with shorter duration of symptoms, suggesting that an earlier diagnosis could also benefit patient response and recovery.

In an attempt to elucidate the consequences of broadening DSM-IV criteria for generalized anxiety disorder, the current study examined prospectively the evolution of GAD symptoms in two groups of diagnosed patients in public and private mental healthcare settings; one group according to the existing DSM-IV criteria and the other according to broader criteria (at least 1 month but less than 6 months of excessive or non-excessive worry and 2 associated symptoms listed on DSM-IV for GAD diagnosis). By using the total HAM-A scores, changes in evolution of anxiety symptoms were studied in both criteria groups under the basis of routine medical care in a 6 month period. Finally, self-reported quality of life, disability and other patient-reported-outcomes were studied as a measure of the overall well-being of GAD patients.

MATERIALS AND METHODOLOGY

Study Design

This was a multicentre, prospective and observational study carried out in outpatient psychiatric clinics between October 2007 and January 2009. The study was approved by the local ethics committee of the Hospital Clínico de San Carlos (Madrid) and was conducted according to the Helsinki declaration for research in the human being. Patients were requested to give written informed consent before taking part in the study. Patients were evaluated at Baseline, 3 and 6 months visits. Functional and clinical outcome measures were completed in all three visits and included the following instruments: Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale, Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (baseline and 6 month visit only), Clinical Global Impression-Severity of Illness Scale, Sleep Scale from Medical Outcomes Study (MOS-sleep), World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II (baseline and 6 month visit only), and the quality of life questionnaire, EQ-5D (all described in detail below). At baseline, socio-demographic data, current therapy and psychiatric and medical illnesses information were collected. For the 3 and 6 months visits, psychiatrists collected data related to patient’s follow-up and current treatments. Participation in the study did not modify the usual clinical management of participating physicians. Psychiatrists participating in the study made a confirmatory diagnosis of GAD in 6 consecutive patients, 3 according to DSM-IV criteria and 3 according to broad criteria. Although patients could have symptoms and receive treatment before entering the study, they hadn’t been diagnosed before by the psychiatrist.

Study Sample

Eligible patients were men and women over 18 years of age that were diagnosed with GAD by a trained psychiatrist at the baseline visit. Exclusion criteria included previous GAD diagnosis, inability or difficulty to understand patient-reported-outcomes questionnaires written in Spanish. Diagnosis was carried out by a trained psychiatrist, familiar with the study procedures, and who worked in an outpatient setting.

A stratified multistage probabilistic sample without replacement was drawn. Sampling frame included all public and private healthcare settings within the 17 regions of Spain. First stage consisted on a selection of the outpatient psychiatry clinics (mental health centres) in each healthcare region. The number of clinics selected in each region was proportional to the region’s population, being the probability of choosing each clinic relative to the population in the area covered by the clinic. In the second stage, one psychiatrist per clinic was chosen randomly within those with previous experience in clinical and epidemiological research in Psychiatry, and with at least 5 year experience in mental health diseases diagnosis. If a selected psychiatrist refused to participate, he or she was replaced by another from the same clinic (also selected randomly). Finally, patients were enrolled at the third stage by a systematic sampling strategy. Participant psychiatrists were asked to invite in a consecutive manner those patients from the daily list of appointments that fulfilled the inclusion criteria. Psychiatrists were encouraged to maintain the above mentioned proportion of 3 subjects diagnosed following DMS-IV criteria and 3 subjects diagnosed following the broad criteria.

Sample size was calculated taking into account study’s main variable: evolution of anxiety symptoms according to the total HAM-A scores for each patient group. A sample of 3400 evaluable patients was estimated assuming a 2-tailed 95% confidence interval for the total HAM-A scores lower than 0.25 points from the observed mean. Based on the results of a previous study, a standard deviation lower than 8 was assumed [4].

Diagnostic Assessments

GAD was diagnosed following the DSM-IV criteria (DSM-IV criteria group) in one group [1]. The other group (broad criteria group) was diagnosed according to broader criteria consisting on shortening of anxiety duration from “at least 6 months” to “at least 1 month (but less than 6 months)”, including excessive or non-excessive worry and reducing the associated symptoms from a minimum of 3 to a minimum of 2. As described previously, patients were diagnosed by a trained psychiatrist.

Clinical and Functional Outcome Measures

Hamilton Anxiety Rating Scale (HAM-A): The validated Spanish version of the HAM-A scale was used to evaluate the evolution of anxiety symptoms during all 3 visits of the study [19]. The patient was interviewed about the anxiety symptoms experienced the previous week. The HAM-A scales includes 14 items, each of them rates from 0 (absence) to 4 (severe). The total score comes from the addition of all 14 items with a maximum of 56. Scores higher than 24 were considered as severe anxiety; between 16 and 24, moderate; between 10 and 15, mild; and below 9, no anxiety. A psychic anxiety sub domain (addition of items 1-6 and 14) and a somatic anxiety sub domain (addition of items 7-13) were also calculated, with a maximum value of 28 in each subscale.

Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS): The validated Spanish version of the MADRS scale was used to measure the intensity of depression symptoms [19]. This observer-rated depression scale consists on 10 items regarding different depressive symptoms, each item being scored from 0 to 6 depending on the severity of symptoms; the total score results from adding the score of each item, obtaining a minimum of 0 (no symptoms) and a maximum of 60 (very severe).

Clinical Global Impression-Severity of Illness Scale (CGI-S): Participant psychiatrists evaluated patient’s global severity with the CGI-S scale, which rates illness severity from 0 to 7, where 0 was considered as “not evaluated”, 1 as “no disease”, 2 “borderline ill”, 3 “mildly ill”, 4 “moderately ill”, 5 “markedly ill”, 6 “severely ill”, and 7 “extremely ill” [20].

Sleep Scale from Medical Outcomes Study (MOS-SLEEP): MOS-SLEEP scale evaluates the impact or interference with sleep of any disease or treatment. This 12-item scale is made up of 7 subscales and 2 overall index scores. The 7 subscales are sleep disturbance (4 items), snoring (1 item), awaken short of breath or with headache (1 item), quantity of sleep (1 item), optimal sleep (1 item), sleep adequacy (2 items), and somnolence (3 items). This scale also has a sleep problems index, rated from 0 (no interference) to 100 (maximum interference), and a sleep problems subscale. Each item is rated independently with more interference scoring higher, except for the sleep adequacy and quantity and optimal sleep subscales [21, 22].

World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II (WHO-DAS II): The WHO-DAS II is a psychometric instrument that measures day to day functioning and disability in the following six activity domains: understanding and communicating, moving and getting around, self care, getting along with people, work activities, and participation in society. The 12-item WHO-DAS II scale is rated from 1 (none or nothing) to 5 (extreme or inability to perform a given task). The total calculated score ranges from 0 to 100, with higher scores indicating higher degrees of disability, for the total scale as well as for each subscale [23].

EQ-5D: This is a standard self-reported quality of life questionnaire developed in several European countries and validated for Spain [24]. This questionnaire consists of two parts, the first one aims to evaluate patient’s health profile in five dimensions (mobility, self-care, daily living activities, pain, and anxiety/depression). The patient rates his/her current status as no problems, some/moderate problems, and severe/extreme problems for each dimension. Results are then converted into 1 of the 243 different EQ-5D health state descriptions which are used to calculate a unique index or tariff, between 1 (as healthy as possible) and 0 (usually equivalent to death). This index is used to calculate the time-trade off tariff which allows calculating quality-adjusted-life-year (QALY) gain (further explanation below). The second part consists on a visual analogue scale (VAS or thermometer) in which the patient has to rate his health status between 0 (equivalent to death) and 100 (the best possible healthy status).

Statistical Analysis

For statistical analysis, last observation carried forward approach was used for those patients for whom data from the 6 months visit were missing. If the only missing data was that from the 3 months visit, this was estimated proportionally to the change observed at the 6 months visit, given that the missing data at 3 month visit were completely at random. Patients were considered to respond to treatment when a higher than 50% reduction was observed for the total HAM-A scale score at the study final visit when compared to that of the baseline visit.

Descriptive statistics were prepared for the continuous variables in the study, including the assessment of central position and dispersion (two-tailed 95% confidence interval). The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test was applied to check adjustment of data to a Gaussian distribution. For categorical variables absolute and relative frequencies were calculated. For comparisons, Student t tests and chi-square test were used for continuous and categorical variables, respectively, to test homogeneity of baseline data between groups. Analysis of Covariance (ANCOVA) or binary logistic regression models were fitted comparing DSM-IV criteria versus broad criteria groups in most variables adjusting by baseline scoring, sex, age, body mass index, educational level, marital status and percentage of patients with comorbid major depression or depressive disorder. Analysis of variance (ANOVA) was applied for quantitative measures and Chi square (McNemar’s test) for qualitative measures in case of paired comparisons.

The clinical relevance of observed differences in baseline characteristics was ascertained by means of the effect size that was calculated using the difference of means for each group, divided by the combined standard deviation of the variables [25].

QALYs gain after the 6-months follow-up was calculated from patients’ responses to the EQ-5D as described previously using tariff calculated with this instrument. We used Spanish values for tariffs calculation [24]. Gained QALYs were estimated by using the trapezoidal approach, with baseline and 6- month visit values used as reference values [26].

All statistical tests were two-tailed, and α error of < 0.05 was accepted as statistically significant. Data were analyzed using SAS version 8.2 statistical software.

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

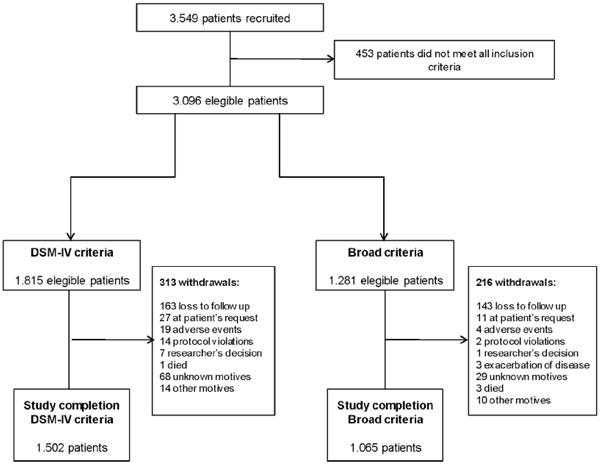

A total of 3,549 patients were finally recruited by 618 psychiatrists in Spanish psychiatric clinics for this observational study. Four hundred and fifty three patients (12.8%) were excluded because they did not meet all inclusion criteria. Remaining patients were diagnosed of GAD according to DSM-IV criteria (1,815 patients) or to broad criteria (1,281 patients) as described on the Methods section. A total of 529 (17.0%) patients drop-out from study, with no significant differences between study groups (DSM-IV criteria: 313 patients, broad criteria: 216 patients; p=0.899) (Fig. 1). However, main reasons for drop-outs were a somewhat different between groups with 52.7% lost to follow-up in DSM-IV group, compared with 67.1% in broad criteria group (p=0.033), and unknown reasons in 22.0% of withdrawals in DSM-IV group compared with 13.6% in broad criteria group (p=0.023). Socio-demographic characteristics are shown in Table 1. The mean age was 45.5 years for the DSM-IV group and slightly lower for the broad criteria group (42.9 years, p<0.001 vs. DSM-IV group). Regarding GAD, all features studied were slightly, but significantly higher in the standard DSM-IV criteria group. Thus, the mean number of anxiety symptoms was 4.7 for the DSM-IV group compared with 4.3 for the broad criteria group (p<0.001). Significant differences were also observed in the percentage of patients presenting with each individual GAD symptom. All HAM-A scores indicated severe anxiety on both patient groups, being the scores in the DSM-IV group significantly higher (Table 1). Likewise, statistical differences were observed at baseline in the CGI and MADRS scales between the two groups. However, the magnitude of the effect was low for all quantitative variables at baseline (Effect size < 0,50 ) so the statistically significant differences observed were of small or negligible clinical relevance.

Baseline Characteristics of Study Subjects by Criteria Group (Mean ± SD)

| DSM-IV Criteria (n=1,815) | Broad Criteria (n=1,264) | P | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Gender (Female) (%) | 1,145 (68.1%) | 748 (64.2%) | 0.029 |

| Age (years) | 45.5 ± 13.0 | 42.9 ± 13.2 | <0.001 |

| BMI (Kg/m2) | 25.4 ± 4.2 | 24.7 ± 3.8 | <0.001 |

| Obesity N (%) § | 184 (10.9) () | 82 (7.0) | <0.001 |

| Highest educational level (%) | <0.001 | ||

| No studies | 75 (4.2) | 40 (3.1) | |

| Elementary school | 1008 (55.6) | 562 (44.6) | |

| High school | 361 (19.9) | 317(25.2) | |

| College or higher | 354 (19.5) | 330 (26.2) | |

| Employment status N (%) | 0.0003 | ||

| Employed | 952 (52.5) | 747 (59.2) | |

| Unemployed | 138 (7.6) | 94 (7.5) | |

| Housewife | 409 (22.6) | 211 (16.7) | |

| Other | 313 (17.3) | 209 (16.6) | |

| Marital status N(%) | 0.004 | ||

| Single | 428(23.6) | 366(29.0) | |

| Married/ Living together | 1121(61.9) | 736(58.4) | |

| Divorced | 179(9.9) | 118 (9.4) | |

| Widowed | 83 (4.6) | 41 (3.3) | |

| Mean number of GAD symptoms | 4.7 ± 1.0 | 4.3 ± 1.2 | <0.001 |

| Symptoms N (%) | |||

| Restlessness | 1504 (90.0) | 977 (86.3) | 0.003 |

| Being easily fatigued | 1065(63.7) | 591 (52.2) | <0.001 |

| Difficulty concentrating | 1351 (80.8) | 852 (75.3) | 0.001 |

| Irritability | 1293 (77.4) | 806 (71.2) | <0.001 |

| Muscle tension | 1300 (77.8) | 804 (71.0) | <0.001 |

| Sleep disturbance | 1414 (84.6) | 866 (76.5) | <0.001 |

| HAM-A | |||

| Total scale score | 26.0 ± 7.0 | 24.4 ± 7.2 | 0.001 |

| Psychic anxiety sub-score | 14.5 ± 3.6 | 13.7 ± 3.7 | <0.001 |

| Somatic anxiety sub-score | 11.5 ± 4.3 | 10.7 ± 4.4 | 0.008 |

| MADRS | 22.4 ± 6.9 | 21.3 ± 7.1 | 0.001 |

| CGI-S | 4.1 ± 0.8 | 4.0 ± 0.8 | 0.002 |

§ Obesity defined as BMI > 30 Kg/m2

HAM-A= Hamilton Rating Scale for Anxiety; MADRS= Montgomery-Asberg Depression Rating Scale; CGI-S= Clinical Global Impression - Severity of Illness Scale.

Step-by-step cohort selection according to inclusion criteria.

Treatment

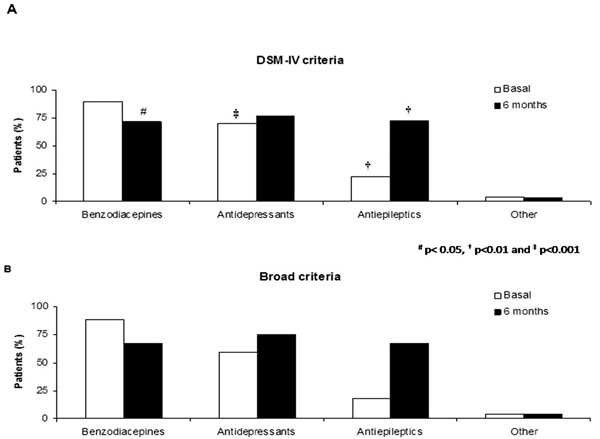

Most patients in both groups (87.9% for DSM-IV; 82.0% for broad criteria) were following a pharmacological treatment in the six months previous to the baseline visit. As described in Fig. (2), benzodiazepines were the most commonly used drugs followed by antidepressants and antiepileptics. At the end of the study, there was an increase in the number of patients under pharmacological treatment (97% in both groups, p<0.001 versus baseline in all cases). The use of antiepileptic drugs increased by 3.2 and 3.8 fold in the DSM-IV and broad criteria groups, respectively, by the end-of-trial (p<0.001 in all cases). The percentage of antiepileptic drugs users in DSM-IV group at baseline and at 6 months was significantly higher, albeit only slightly (p=0.002 in both cases, Fig. 2). Both groups showed a significant reduction in the percentage of benzodiazepines users after 6 months of follow-up (p<0.001), being this reduction even higher in the broad criteria group (p=0.011). Also a slight but statistically significant increase was observed in the percentage of anti-depressive users in both groups (p<0.001, see Fig. 2).

Drugs used for GAD treatment at basal and 6 month visits. A) DSM-IV criteria group. B) Broaden criteria group. Data presented as percentage of patients in each group.

Differences not significant when not indicated. All changes, except for other, were statistically significant when compared to the baseline visit (p<0.001 in all cases). # p< 0.05, † p<0.01 and ‡ p<0.001 when comparing DSM-IV and broad criteria groups in both visits.

Comorbidity

At the study entry, the percentage of subjects in DSM-IV and broad criteria groups that had at least one psychiatric comorbidity was 51.4% and 43.7%, respectively, (p<0.001). Table 2 describes the most frequent psychiatric comorbidities and medical disorders in both study groups. However, neither the mean number of comorbid psychiatric disorders

Most Frequent Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders and Medical Illnesses at Baseline Visit by Criteria Group

| DSM-IV Criteria | Broad Criteria | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Comorbid Psychiatric Disorders | ||||

| Frequency, N (%) | Time (Months) (Mean± SD) | Frequency, N (%) | Time (Months) (Mean± SD) | |

| Major depression | 294 (16.4)† | 5.5 ± 6.1 | 150 (11.9) | 6.2 ± 7.9 |

| Panic disorders | 178 (9.9) | 4.0 ± 4.2 | 108 (8.6) | 3.0 ± 3.8 |

| Social phobia | 138 (7.7) | 4.6 ± 5.2 | 91 (7.2) | 3.3 ± 4.6 |

| Phobias | 125 (7.0) | 4.9 ± 6.1 | 78 (6.2) | 4.6 ± 5.6 |

| Other depressive disorders1 | 110(6.1)* | 5.8 ± 5.2 | 57 (4.5) | 5.2 ± 4.2 |

| Obsessive-compulsive disorder | 59 (3.3) | 7.4 ± 7.1 | 37 (2.9) | 8.5 ± 7.4 |

| Substance abuse | 51(2.8) | 4.6 ± 5.1 | 24 (1.9) | 5.7 ± 5.5 |

| Adjustment disorders | 34(1.9) | 2.8 ± 3.3 | 29 (2.3) | 1.9 ± 2.7 |

| Mean (SD) number of disorders | 1.2 (0.5) | 1.2 (0.5) | ||

| Comorbid Medical Illnesses | ||||

| Mean (SD) number of illnesses | 1.5 (0.9) | 1.5 (0.8) | ||

| Chronic pain, n (%) | 735 (40.9) ‡ | 343(27.3) | ||

| Gastrointestinal diseases, n (%) | 333 (18.6) * | 196 (15.6) | ||

| Cardiovascular diseases, n (%) | 172 (9.6) | 116 (9.2) | ||

| Metabolic diseases, n (%) | 125(7.0) | 80 (6.4) | ||

| Genitourinary tract diseases, n (%) | 84 (4.7) | 43 (3.4) | ||

| Muscular pain, n (%) | 35 (1.9) | 19 (1.5) | ||

SD=Standard deviation. Results are shown as percentage of patients in each group presenting with every illness (frequency) and time from diagnosis till basal visit (in months).

1 Includes depressive disorders different than major depression, dystimia, combined disorders of anxiety and depression, reactive depression, unspecified depressive disorder, secondary depression to abuse of substances/drugs, etc

* p<0.05

† p<0.01

‡ p<0.001 versus Broad criteria group. Not significant when not indicated.

nor the medical illnesses were different between both criteria groups, except for comorbid major depression and other depressive disorders which were slightly more frequent, but statistically significant in DSM-IV group (p<0.01 and p=0.05, respectively, Table 2). Regarding psychiatric disorders, most of them were present around 5 months before the diagnosis of GAD, without significant differences between groups in disease evolution. Major depression and panic disorders were the most frequent comorbid psychiatric disorders in both study groups. For medical illnesses, chronic pain was present in more than half of patients in both groups, although a higher percentage was seen in DSM-IV group; 64.3% versus 52.0%, p<0.001 (Table 2).

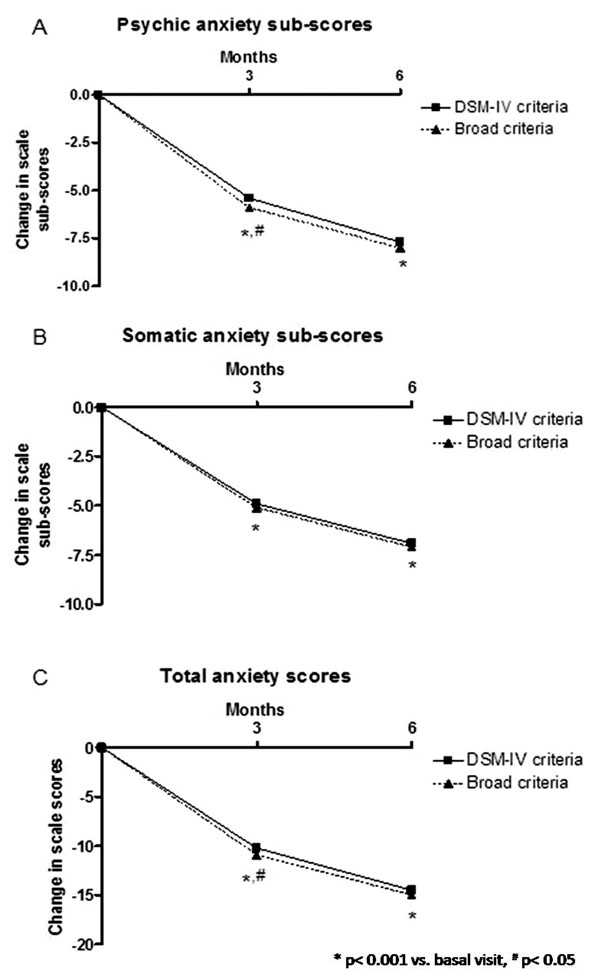

Reduction of Anxiety Symptoms After 6-Month Treatment and Severity of Illness

Anxiety severity was assessed with HAM-A and CGI-S scales at 3 and 6 month visits. Fig. (3) shows the evolution of HAM-A total and sub-scores over study time in the DSM-IV and broad criteria groups. All HAM-A scores improved after 3 and 6 months in both criteria groups. Moreover, the percentage of patients without symptoms of anxiety, showing HAM-A<9, increased up to 22.3% and 31.4% at the 3 month visit for the DSM-IV and broad criteria groups (p<0.001 vs. basal visit in both groups, and p=0.006 between groups), and up to 49% and 58% at the 6 month visit (p<0.001 vs. basal visit in both groups, and p=0.261 between groups), indicating similar results for both groups at the end of the study. Also, patients responding to anxiety treatment increased when considering the responder criteria (>50% reduction of baseline scores); 30.7% and 38.2% for the DMS-IV and broad criteria, respectively, at the 3 months visit (p= 0.004); increasing up to 59.7% in the DMS-IV and 67.7% at the 6 month visit (p=0.103).

Reduction on HAM-A scale and subscale scores at 3 and 6 months visit for both DSM-IV and broad criteria groups. A) Psychiatric anxiety sub-scores, B) Somatic anxiety sub-scores and C) Total scores.

Data presented as change in scale score. * p< 0.001 vs. basal visit, # p< 0.05 DSM-IV vs. broad criteria scores.

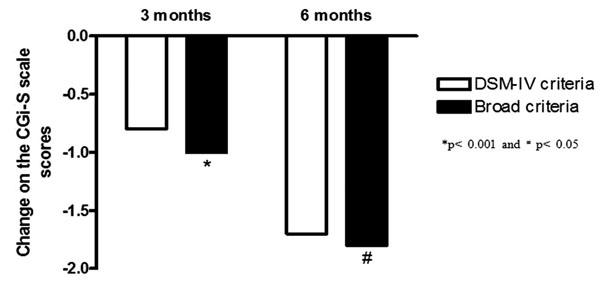

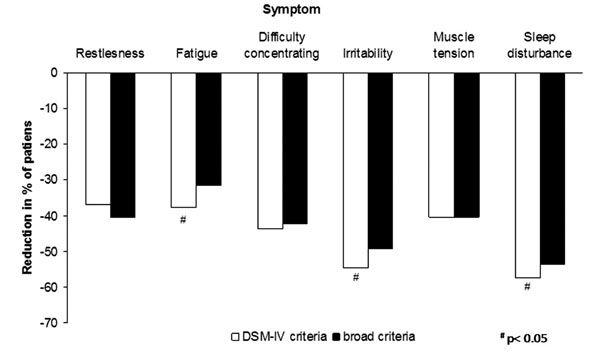

With respect to the observed results for the CGI-S scores (Fig. 4), differences between criteria groups were statistically significant at the study time points. Regarding each GAD symptom, Fig. (5) shows the reduction in the percentage of patients presenting with each anxiety symptom. Individually, significant improvements were observed for each anxiety symptom in both study groups. However, higher significant reductions were observed in DSM-IV group for the following symptoms: fatigue, irritability and sleep disturbance (p<0.05 in all cases, Fig. 5).

Score evolution for the CGI-S scale scores by study group.

All changes were statistically significant when compared to the basal visit (p<0.001). *p< 0.001 and # p< 0.05 when comparing DSM-IV and broad criteria groups.

Reduction versus baseline in the percentage of patients presenting with each individual anxiety symptom at the 6 months visit by study group.

All changes were statistically significant when compared within group to the baseline visit (p<0.001). # p< 0.05 when comparing DSM-IV and broad criteria groups.

In this study, depression symptoms were evaluated using the MADRS. When compared to scores at baseline visit (Table 1), patients in both criteria groups improved their MADRS scores with a mean reduction of 12.1 and 12.5 points for the DMS-IV and broad criteria groups, respectively (p=0.264 DSM-IV vs. broad criteria).

Functional Outcome Measures

MOS-Sleep scale scores revealed an overall improvement in sleep patterns over study time in both criteria group. As described in Table 3, all sleep domains in the MOS-Sleep scale changed significantly after 6 months when compared to basal visit scores. Differences between the DSM-IV and broad criteria groups were observed for the total score (p= 0.018), sleep disturbance domain (p=0.012), sleep quantity (p=0.016), sleep adequacy (p=0.031), and sleep problems (p=0.019) scores, always favouring the broad criteria group.

Changes on self-reported Health Related Quality of Life Scores Over Study Time

| Scale | DSM-IV Criteria (n=1,815) | Broad Criteria (n=1,264) | Change Adjusted Difference [CI 95%], p | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Baseline | Change at 6 Months | Baseline | Change at 6 Months | ||

| MOS-SLEEP (summary) | 51.9 | -26.7‡ | 50.2 | -28.3‡ | 1.6 [0.3;2.9], 0.018 |

| Sleep disturbance | 55.8 | -29.7‡ | 53.7 | -31.5‡ | 1.8 [0.4;3.3], 0.012 |

| Snoring | 32.0 | -7.8‡ | 28.8 | -7.9‡ | 0.1 [-1.5;1.6], 0.947 |

| Awakening short of breath | 34.2 | -19.0‡ | 33.6 | -19.5‡ | 0.5 [-1.0; 2.0], 0.489 |

| Sleep quantity | 5.6 | 1.4‡ | 5.7 | 1.5‡ | -0.1 [-0.2;-0.0], 0.016 |

| Sleep adequacy | 33.1 | 32.8‡ | 34.7 | 35.0‡ | -2.2 [-4.2;-0.2], 0.031 |

| Somnolence | 37.4 | -14.9‡ | 35.7 | -15.2‡ | 0.2 [-1.0;1.5], 0.699 |

| Sleep problems | 51.8 | -26.5‡ | 50.3 | -28.1‡ | 1.7 [0.3;3.0], 0.019 |

| EQ-5D | |||||

| Health status (VAS) | 46.2 | 24.1‡ | 46.7 | 25.5‡ | -1.4 [ -2.7; -0.2], 0.028 |

| QALYs gain1 | - | 0,103 | - | 0,101 | 0,002 [-0,007; 0,011], 0.654 |

| Domain2 | |||||

| Mobility | 38.0 | -12.1‡ | 34.3 | -13.3‡ | 1.2 [-1.4; 3.8], 0.359 |

| Self-care | 33.0 | -10.8‡ | 33.7 | -11.9‡ | 1.1 [-1.0; 3.1], 0.311 |

| Daily living activities | 88.2 | -40.7‡ | 86.1 | -45.1‡ | 4.4 [0.3; 8.5], 0.035 |

| Pain/discomfort | 74.3 | -33.7‡ | 71.8 | -35.7‡ | 2.1 [-1.7; 5.8], 0.286 |

| Mood (anxiety/depression) | 95.0 | -49.4‡ | 94.4 | -53.8‡ | 4.3 [0.1; 8.6], 0.044 |

MOS-SLEEP: Sleep Scale from Medical Outcomes Study; VAS: Visual analogue scale, QALYs: Quality-adjusted life-year. CI=Confidence interval

‡ p< 0.001 vs. basal visit.

1 10.083 QALY equivalent to 1 month of full healthy life

2 Values are % of severe problem in each domain.

Health-related quality of life was measured by the EQ-5D questionnaire. As seen in Table 3, both the health status (visual analogue scale) and the frequency of severe problems in each domain had significantly improved at the 6 month visit in both study groups (p<0.001 in all cases). Also, comparisons between both criteria groups in quality-of-life gain by domain were significant in favour of the broad criteria group in health status, daily living activities and mood status. Mean QALYs gain at the 3 month and 6 month visits were 0.034 and 0.103 years, respectively, for the DSM-IV criteria group and 0.034 (3 month) and 0.101 (6 month) for the broad criteria patients, without statistical significance between groups (Table 3). At the 6 month visit, the percentage of patients reporting an improvement in their health status as compared with that of one year earlier increased by 13.8% for the DSM-IV criteria group, and 16.6% for the broad criteria group (differences not significant).

For measuring the disability degree in both groups of patients, the WHO-DAS scale was used. As shown in Table 4, there was a significant improvement in all 7 domains of the WHO-DAS II scale after the 6 month follow-up in both criteria groups. The improvements were not significantly different in the DSM-IV group when compared to the new criteria group except for household activity domain, in which the improvement in the DSM-IV group was significantly better when compared to the broad criteria group. Nevertheless, a trend toward statistical significance was observed in the total scoring of the disability scale favouring broad criteria group.

Changes on Disability Levels on all Domains of the WHO-DAS II Scale Over Study Time by Groups

| DSM-IV Criteria (n=1,815) | Broad Criteria (n=1,264) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Basal | Change at 6 Months | Basal | Change at 6 Months | Change Adjusted Difference [CI95%], p | |

| WHO-DAS II domain | |||||

| Understanding/ communicating | 43.6 | -22.1‡ | 42.9 | -22.9‡ | 0.8 [-0.6; 2.2], 0.258 |

| Getting around | 35.0 | -15.0‡ | 33.2 | -15.6‡ | 0.6 [-0.8; 1.9], 0.409 |

| Self care | 20.6 | -5.3‡ | 20.3 | -5.9‡ | 0.6 [-0.2; 1.5], 0.154 |

| Getting along with people | 49.9 | -23.7‡ | 47.9 | -23.6‡ | -0.1 [-2.0; 1.8], 0.911 |

| Household activities | 53.1 | -21.2‡ | 51.6 | -24.0‡ | 2.9 [0.7; 5.1], 0.010 |

| Work activities | 60.9 | -29.6‡ | 58.8 | -31.5‡ | 1.9 [-0.5; 4.3], 0.120 |

| Participation in society | 57.5 | -26.4‡ | 55.5 | -28.1‡ | 1.7 [-0.0; 3.4], 0.051 |

| Total score | 32.1 | -14.4‡ | 31.0 | -15.2‡ | 0.8 [-0.1; 1.7], 0.086 |

WHO-DAS II: World Health Organization Disability Assessment Schedule II

‡ p< 0.001 vs. basal visit.

DISCUSSION

This real world prospective study in usual medical practice has shown that broadening of GAD DSM-IV diagnostic criteria, by reducing the duration of excessive or non-excessive worry to one month and associated symptoms to two, does not significantly affect patient’s responsiveness to psychiatrist-prescribed therapy. After 6 months, both groups had a significant improvement in GAD symptoms. The patient sample of this study seems to be similar to other GAD populations presented in previous studies, with a higher prevalence among women and among those aged above 25 years [4, 18]. The most frequent comorbid psychiatric disorder was major depression; however, its presence was somewhat smaller than the observed in other studies, if we take into account major depression only [27].

The main goal when treating a GAD patient is to improve the symptoms, hopefully leading in the long-term to their complete remission and to recovery of patient’s functionality. Several guidelines recommend antidepressants, such as the selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and the serotonin noradrenalin reuptake inhibitors, and antiepileptics as first line treatments, and benzodiazepines as second-line treatment [28, 29]. Although patients in this study received a confirmatory diagnosis of GAD, a high percentage of them were already following a therapy recommended for GAD at baseline. These results suggest that, in our sanitary context, general practitioners and/or family physicians start treatment to control anxiety symptoms, mostly with benzodiazepines, at patients first complaint. The general practitioner/family physician usually refers those patients with lower treatment response than expected to the psychiatrist. It should be taken into account that refractory patients may be difficult to manage at the primary care level in the Spanish Health System. One of the reasons is the brief period of time devoted by physicians to each patient visit in the Spanish primary health care level, as described by Duran et al. [30].

Other studies have explored the consequences of broadening DSM-IV diagnostic criteria for GAD [3, 13, 15-16, 31]. Most of them have considered a reduction in the duration criteria [3, 16], the excessiveness of worry [31], and the number of associated symptoms. A possible learning from all of them is that the socio-demographic characteristics between the populations diagnosed with broad or strict DSM-IV criteria are not substantially different. As expected, the broadening of DSM-IV GAD criteria results in an increase in the point-prevalence to more than double [15-16]. Ruscio et al. [16] concluded that the increase was mainly due to the reduction of minimum duration to one month. In regards to GAD’s severity, Ruscioet al. [16] observed a tendency to reduced severity for the broad criteria group, however, it did not reach statistical significance. In the present study we have observed a similar tendency suggesting that patients diagnosed with broader GAD criteria present a slightly less severe form of the disease.

Every study that has investigated the possibility of broadening the DSM-IV criteria has done it retrospectively [13, 15, 16, 27, 31, 32]. The present study is the first one to compare two groups of GAD patients with DSM-IV and broader criteria following a prospective design. According to our results, broadening of GAD diagnostic criteria does not affect the response to the prescribed therapy, since HAM-A scores, total and domains, improved similarly in both groups, and so did the presence of GAD symptoms (Fig. 5). Moreover, a significant improvement was perceived by physicians (CGI-S scores) at the end of the study. GAD is an impairing disease that reduces patient’s functionality at several levels. The influence of broader GAD diagnostic criteria in patient’s disability has been studied previously by Leeet al. (2009) and Kessler (2005). Lee et al. [15] observed an increase in the Sheehan Disability Scale score when increasing time for the duration criteria although it was not statistically significant. The same observation was made by Kessler et al. [17] with data from the NCS. Parallel to their clinical improvement, patients in our study experienced an improvement in the studied quality of life variables. Health status improvements in our study were similar to those observed in primary care patients receiving treatment over six months for their GAD [33]. The biggest improvements were observed in the daily living activities and mood domains of the EQ-5D. QALYs gain observed corresponded to more than one month of perfect health for both groups; which were similar in magnitude to that observed in other health conditions such as trigeminal neuralgia, successfully treated with pregabalin [34]. All other dimensions of functionality included in the WHO DAS-II scale, and sleep scale were substantially ameliorated in both study groups by the end-of-trial; however, the differences in the magnitude of these improvements for both groups were hardly meaningful from a clinical point of view.

Results from this study should be interpreted bearing in mind its observational design with its inherent limitations. Since this study is based on out-patient psychiatric clinics, patients included in this study might not be representative of the whole GAD population, since psychiatrists could deal with more severe and refractory cases [4]. Also, due to the high degree of expertise required for participant psychiatrists, diagnosis in our study may have been more accurate than in other settings, such as primary care. A consequence of broadening GAD criteria in other healthcare settings could be the difficulty in distinguishing GAD from adjustment disorders or situational stress reactions by other less trained physicians. In this study there was a high proportion of patients treated with antiepileptics; that could be explained by the fact that most subjects included in the study were non responders to recommended first line drug treatment according to the European guidelines on the treatment and management of GAD patients [29]. Finally, as this was a real world prospective study we did not have a control group so further clinical research with randomized controlled studies and newly diagnosed patients needs to be carried out to confirm the consequences of broadening the criteria.

CONCLUSION

Broadening criteria for GAD diagnosis, by reducing excessive and non-excessive anxiety and worry duration to one month and the number of associated symptoms to two, captures a similar population of patients compared to the one identified by applying standard DSM-IV criteria. Broadening diagnostic criteria is able to identify the core symptoms of GAD according to the DSM-IV criteria and could lead to an earlier diagnosis.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

Funding for this study was provided by Pfizer Spain; Pfizer Spain participated in the idea and design of the study. Enrique Álvarez, Jose L. Carrasco and José M. Olivares declare not to have any conflict of interests as a consequence of participating in this study. Inma Vilardaga was employed of the European Biometric Institute, a consulting agency which was responsible for logistic of study and analysis of data. María Perez and Vanessa López-Gómez are employed by Pfizer Spain, the body funding the study.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Authors wish to thank to Javier Rejas MD for his contribution and support in the design of the study and interpretation of data. Also, we thank Margarita González-Adalid. for her assistance on writing this manuscript.